All the way back in 2014, the web passed a pretty significant milestone: 1 billion websites. Of course, fewer than 200 million of these are actually active as of 2019, but there’s an important underlying point. People love to create. If the current digital age that we live in has taught us anything, it’s that it’s never been as easy to get information and ideas out into the world.

Understandably, this ability has been used – and often misused. Overloaded, convoluted websites are par for the course, with a common tactic for website renewal being to simply update them with a new coat of paint while ignoring the swirling pile of outdated and poorly organized content below.

So what are you supposed to do when trying to address this problem on your own website or digital project? Well, there’s a fairly robust technique called top tasks management. Here, we’ll go over exactly what it is and how you can use it.

Getting to grips with top tasks

Ideally, all websites would be given regular, comprehensive reviews. Old content could be revisited and analyzed to see whether it’s still actually serving a purpose. If not, it could be reworked or just removed entirely. Based on research, content creators could add new content to address user needs. Of course, this is just the ideal. The reality is that there’s never really enough time or resource to manage the growing mass of digital content in this way. The solution is to hone in on what your users actually use your website for and tailor the experience accordingly by looking at top tasks.

What are top tasks? They're basically a small set of tasks (typically around 5, but up to 10 is OK too) that are most important to your users. The thinking goes that if you get these core tasks right, your website will be serving the majority of your users and you’ll be more likely to retain them. Ignore top tasks (and any sort of task analysis), and you’ll likely find users leaving your website to find something else that better fits their needs.

The counter to top tasks is tiny tasks. These are everything on a website that’s not all that important for the people actually using it. Commonly, tiny tasks are driven more by the organization’s needs than those of the users. Typically, the more important a task is to a user, the less information there is to support it. On the other hand, the less important a task is to a user, the more information there is. Tiny tasks stem very much from ‘organization first’ thinking, wherein user needs are placed lower on the list of considerations.

According to Jerry McGovern (who penned an excellent write-up of top tasks on A List Apart), the top tasks model says “Focus on what really matters (the top tasks) and defocus on what matters less (the tiny tasks).”

How to identify top tasks

Figuring out your top tasks is an important step in clearing away the fog and identifying what actually matters to your users. We’ll call this stage of the process task discovery, and these are the steps:

- Gather: Work with your organization to gather a list of all customer tasks

- Refine: Take this list of tasks to a smaller group of stakeholders and work it down into a shortlist

- User feedback: Go out to your users and get a representative sample to vote on them

- Finalise: Assemble a table of tasks with the one with the highest number of votes at the top and the lowest number of votes at the bottom

We’ll go into detail on the above steps, explaining the best way of handling each one. Keep in mind that this process isn’t something you’ll be able to complete in a week – it’s more likely a 6 to 8-week project, depending on the size of your website, how large your user base is and the receptiveness of your organization to help out.

Step 1: Gather – Figure out the long list of tasks

The first part of the task process is to get out into the wider organization and discover what your users are actually trying to accomplish on your website or by using your products. It’s all about getting into the minds of your users – trying to see the world through their eyes, effectively.

If you’re struggling to think of places where you might find customer tasks, here are some of the best sources:

- Analytics: Take a deep dive into the analytics of your website or product to find out how people are using them. For websites, you’ll want to look at pages with high traffic and common downloads or interactions. The same applies to products – although the data you have access to will depend on the analytics systems in place.

- Customer support teams: Your own internal support teams can be a great source of user tasks. Support teams commonly spend all day speaking to users, and as a result, are able to build up a cohesive understanding of the types of tasks users commonly attempt.

- Sales teams: Similarly, sales teams are another good source of task data. Sales teams typically deal with people before they become your users, but a part of their job is to understand the problems they’re trying to solve and how your website or product can help.

- Direct customer feedback: Check for surveys your organization has run in the past to see whether any task data already exists.

- Social media: Head to Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn to see what people are talking about with regards to your industry. What tasks are being mentioned?

It’s important to note that you need to cast a wide net when gathering task data. You can’t just rely on analytics data. Why? Well, downloads and page visits only reflect what you have, but not what your users might actually be searching for.

As for search, Jerry McGovern explains why it doesn’t actually tell the entire story: “When we worked on the BBC intranet, we found they had a feature called “Top Searches” on their homepage. The problem was that once they published the top searches list, these terms no longer needed to be searched for, so in time a new list of top searches emerged! Similarly, top tasks tend to get bookmarked, so they don’t show up as much in search. And the better the navigation, the more likely the site search is to reflect tiny tasks.”

At the end of the initial task-gathering stage you should be left with around 300 to 500 tasks. Of course, this can scale up or down depending on the size of the website or product.

Step 2: Refine – Create your shortlist

Now that you’ve got your long list of tasks, it’s time to trim them back until you’ve got a shortlist of 100 or less. Keep in mind that working through your long list of tasks is going to take some time, so plan for this process to take at least 4 weeks (but likely more).

It’s important to involve stakeholders from across the organization during the shortlist process. Bring in people from support, sales, product, marketing and leadership areas of the organization. In addition to helping you to create a more concise and usable list, the shortlist process helps your stakeholders to think about areas of overlap and where they may need to work together.

When working your list down to something more usable, try and consolidate and simplify. Stay away from product names as well as internal organization and industry jargon. With your tasks, you essentially want to focus on the underlying thing that a user is trying to do. If you were focusing on tasks for a bank, opt for “Transactions” instead of “Digital mobile payments”. Similarly, bring together tasks where possible. “Customer support”, “Help and support” and “Support center” can all be merged.

At a very technical level, it also helps to avoid lengthy tasks. Stick to around 7 to 8 words and try and avoid verbs, using them only when there’s really no other option. You’ll find that your task list becomes quite to navigate when tasks begin with “look”, “find” and “get”. Finally, stay away from specific audiences and demographics. You want to keep your tasks universal.

Step 3: User feedback – Get users to vote

With your shortlist created, it’s time to take it to your users. Using a survey tool like Optimal's Surveys, add in each one of your shortlisted tasks and have users rank 5 tasks on a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 being the most important and 1 being the least important.

If you’re thinking that your users will never take the time to work through such a long list, consider that the very length of the list means they’ll seek out the tasks that matter to them and ignore the ones that don’t.

Step 4: Finalize – Analyze your results

Now for the task analysis side of the project. What you want at the end of the user survey end of the project is a league table of entire shortlist of tasks. We’re going to use the example from Cisco’s top tasks project, which has been documented over at A List Apart by Gerry McGovern (who actually ran the project). The entire article is worth a read as it covers the process of running a top task project for a large organization.

Here’s what a league table of the top 20 tasks looks like from Cisco:

Here’s the breakdown of the vote for Cisco’s tasks:

- 3 tasks got the first 25 percent of the vote

- 6 tasks got 25-50 percent of the vote

- 14 tasks got 50-75 percent of the vote

- 44 tasks got 75-100 percent of the vote

While the pattern may seem surprising, it’s actually not unusual. As Jerry explains: “We have done this process over 400 times and the same patterns emerge every single time.”

Final thoughts

Focusing on top tasks management is really a practice that needs to be conducted on a semi-regular basis. The approach benefits organizations in a multitude of ways, bringing different teams and people together to figure out how to best address why your users are coming to your website and what they actually need from you.

As we explained at the beginning of this article, top tasks is really about clearing away the fog and understanding on what really matters. Instead of spreading yourself thin and focusing on a host of tiny tasks, hone in on those top tasks that actually matter to your users.

Understanding how to improve your website

The top tasks approach is an effective way of giving you a clear idea of what you should be focusing on when designing or redesigning your website, but this should really just be one aspect of the work you do.

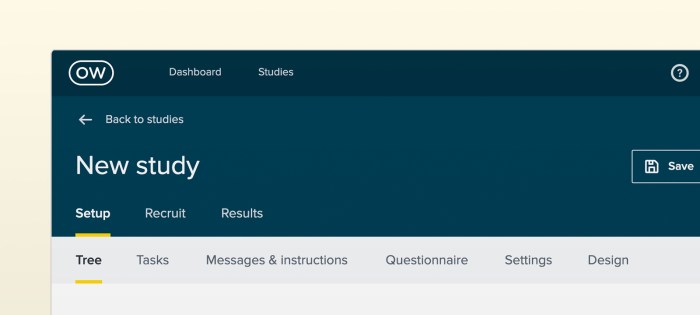

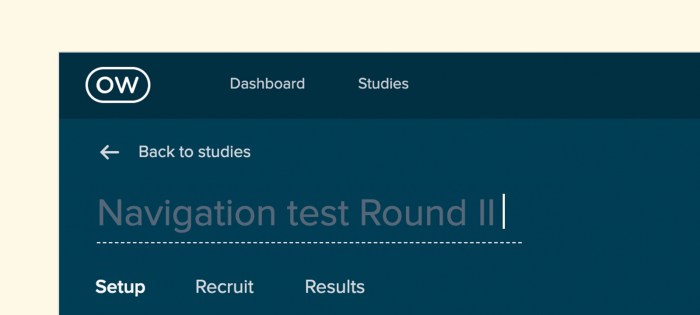

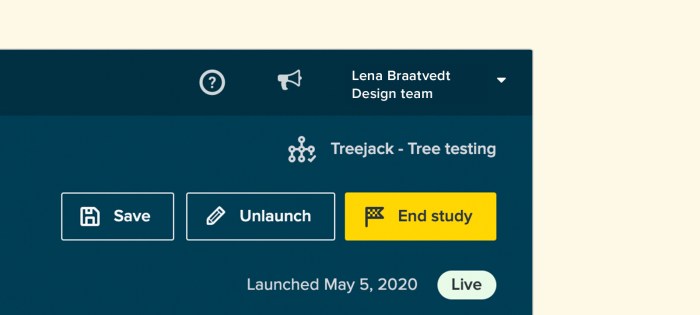

Utilizing a host of other UX research methods can give you a much more comprehensive idea of what’s working and what’s not. With card sorting, for example, you can learn how your users think the content on your website should be arranged. Then, with this data in hand, you can use tree testing to assemble draft structures of your website and test how people navigate their way through it. You can keep iterating on these structures to ensure you’ve created the most user-friendly navigation.

Take a look at our 101 guides to learn more about card sorting and tree testing, as well as the other user research methods you can use to make solid improvements to your website. If you’d rather just start putting methods into practice using user research tools, take our UX platform for a spin for free here.