Optimal Blog

Articles and Podcasts on Customer Service, AI and Automation, Product, and more

A year ago, we looked at the user research market and made a decision.

We saw product teams shipping faster than ever while research tools stayed stuck in time. We saw researchers drowning in manual work, waiting on vendor emails, stitching together fragmented tools. We heard "should we test this?" followed by "never mind, we already shipped."

The dominant platforms got comfortable. We didn't.

Today, we're excited to announce Optimal 3.0, the result of refusing to accept the status quo and building the fresh alternative teams have been asking for.

The Problem: Research Platforms Haven't Evolved

The gap between product velocity and research velocity has never been wider. The situation isn't sustainable. And it's not the researcher's fault. The tools are the problem. They’re:

- Built for specialists only - Complex interfaces that gatekeep research from the rest of the team

- Fragmented ecosystems - Separate tools for recruitment, testing, and analysis that don't talk to each other

- Data in silos - Insights trapped study-by-study with no way to search across everything

- Zero integration - Platforms that force you to abandon your workflow instead of fitting into it

These platforms haven't changed because they don't have to, so we set out to challenge them.

Our Answer: A Complete Ecosystem for Research Velocity

Optimal 3.0 isn't an incremental update to the old way of doing things. It's a fundamental rethinking of what a research platform should be.

Research For All, Not Just Researchers.

For 18 years, we've believed research should be accessible to everyone, not just specialists. Optimal 3.0 takes that principle further.

Unlimited seats. Zero gatekeeping.

Designers can validate concepts without waiting for research bandwidth. PMs can test assumptions without learning specialist tools. Marketers can gather feedback without procurement nightmares. Research shouldn't be rationed by licenses or complexity. It should be a shared capability across your entire team.

A Complete Ecosystem in One Place.

Stop stitching together point solutions.Optimal 3.0 gives you everything you need in one platform:

Recruitment Built In Access millions of verified participants worldwide without the vendor tag. Target by demographics, behaviors, and custom screeners. Launch studies in minutes, not days. No endless email chains. No procurement delays.

Testing That Adapts to You

- Live Site Testing: Test any URL, your production site, staging, or competitors, without code or developer dependencies

- Prototype Testing: Connect Figma and go from design to insights in minutes

- Mobile Testing: Native screen recordings that capture the real user experience

- Enhanced Traditional Methods: Card sorting, tree testing, first-click tests, the methodologically sound foundations we built our reputation on

Learn more about Live Site Testing

AI-Powered Analysis (With Control) Interview analysis used to take weeks. We've reduced it to minutes.

Our AI automatically identifies themes, surfaces key quotes, and generates summaries, while you maintain full control over the analysis.

As one researcher told us: "What took me 4 weeks to manually analyze now took me 5 minutes."

This isn't about replacing researcher judgment. It's about amplifying it. The AI handles the busywork, tagging, organizing, timestamping. You handle the strategic thinking and judgment calls. That's where your value actually lives.

Learn more about Optimal Interviews

Chat Across All Your Data Your research data is now conversational.

Ask questions and get answers instantly, backed by actual video evidence from your studies. Query across multiple Interview studies at once. Share findings with stakeholders complete with supporting clips.

Every insight comes with the receipts. Because stakeholders don't just need insights, they need proof.

A Dashboard Built for Velocity See all your studies, all your data, in one place. Track progress across your entire team. Jump from question to insight in seconds. Research velocity starts with knowing what you have.

Integration Layer

Optimal 3.0 fits your workflow. It doesn't dominate it. We integrate with the tools you already use, Figma, Slack, your existing tech stack, because research shouldn't force you to abandon how you work.

What Didn't Change: Methodological Rigor

Here's what we didn't do: abandon the foundations that made teams trust us.

Card sorting, tree testing, first-click tests, surveys, the methodologically sound tools that Amazon, Google, Netflix, and HSBC have relied on for years are all still here. Better than ever.

We didn't replace our roots. We built on them.

18 years of research methodology, amplified by modern AI and unified in a complete ecosystem.

Why This Matters Now

Product development isn't slowing down. AI is accelerating everything. Competitors are moving faster. Customer expectations are higher than ever.

Research can either be a bottleneck or an accelerator.

The difference is having a platform that:

- Makes research accessible to everyone (not just specialists)

- Provides a complete ecosystem (not fragmented point solutions)

- Amplifies judgment with AI (instead of replacing it)

- Integrates with workflows (instead of forcing new ones)

- Lets you search across all your data (not trapped in silos)

Optimal 3.0 is built for research that arrives before the decision is made. Research that shapes products, not just documents them. Research that helps teams ship confidently because they asked users first.

A Fresh Alternative

We're not trying to be the biggest platform in the market.

We're trying to be the best alternative to the clunky tools that have dominated for years.

Amazon, Google, Netflix, Uber, Apple, Workday, they didn't choose us because we're the incumbent. They chose us because we make research accessible, fast, and actionable.

"Overall, each release feels like the platform is getting better." — Lead Product Designer at Flo

"The one research platform I keep coming back to." — G2 Review

What's Next

This launch represents our biggest transformation, but it's not the end. It's a new beginning.

We're continuing to invest in:

- AI capabilities that amplify (not replace) researcher judgment

- Platform integrations that fit your workflow

- Methodological innovations that maintain rigor while increasing speed

- Features that make research accessible to everyone

Our goal is simple: make user research so fast and accessible that it becomes impossible not to include users in every decision.

See What We've Built

If you're evaluating research platforms and tired of the same old clunky tools, we'd love to show you the alternative.

Book a demo or start a free trial

The platform that turns "should we?" into "we did."

Welcome to Optimal 3.0.

Topics

Research Methods

Popular

All topics

Latest

How to interpret your card sort results Part 1: open and hybrid card sorts

Cards have been created, sorted and sorted again. The participants are all finished and you’re left with a big pile of awesome data that will help you improve the user experience of your information architecture. Now what?Whether you’ve run an open, hybrid or closed card sort online using an information architecture tool or you’ve run an in person (moderated) card sort, it can be a bit daunting trying to figure out where to start the card sort analysis process.

About this guide

This two-part guide will help you on your way! For Part 1, we’re going to look at how to interpret and analyze the results from open and hybrid card sorts.

- In open card sorts, participants sort cards into categories that make sense to them and they give each category a name of their own making.

- In hybrid card sorts, some of the categories have already been defined for participants to sort the cards into but they also have the ability to create their own.

Open and hybrid card sorts are great for generating ideas for category names and labels and understanding not only how your users expect your content to be grouped but also what they expect those groups to be called.In both parts of this series, I’m going to be talking a lot about interpreting your results using Optimal Workshop’s online card sorting tool, OptimalSort, but most of what I’m going to share is also applicable if you’re analyzing your data using a spreadsheet or using another tool.

Understanding the two types of analysis: exploratory and statistical

Similar to qualitative and quantitative methods, exploratory and statistical analysis in card sorting are two complementary approaches that work together to provide a detailed picture of your results.

- Exploratory analysis is intuitive and creative. It’s all about going through the data and shaking it to see what ideas, patterns and insights fall out. This approach works best when you don’t have the numbers (smaller sample sizes) and when you need to dig into the details and understand the ‘why’ behind the statistics.

- Statistical analysis is all about the numbers. Hard data that tells you exactly how many people expected X to be grouped with Y and more and is very useful when you’re dealing with large sample sizes and when identifying similarities and differences across different groups of people.

Depending on your objectives - whether you are starting from scratch or redesigning an existing IA - you’ll generally need to use some combination of both of these approaches when analyzing card sort results. Learn more about exploratory and statistical analysis in Donna Spencer’s book.

Start with the big picture

When analyzing card sort results, start by taking an overall look at the results as a whole. Quickly cast your eye over each individual card sort and just take it all in. Look for common patterns in how the cards have been sorted and the category names given by participants. Does anything jump out as surprising? Are there similarities or differences between participant sorts? If you’re redesigning an existing IA, how do your results compare to the current state?If you ran your card sort using OptimalSort, your first port of call will be the Overview and Participants Table presented in the results section of the tool.If you ran a moderated card sort using OptimalSort’s printed cards, now is a good time to double check you got them all. And if you didn’t know about this handy feature of OptimalSort, it’s something to keep in mind for next time!The Participants Table shows a breakdown of your card sorting data by individual participant. Start by reviewing each individual card sort one by one by clicking on the arrow in the far left column next to the Participants numbers.

From here you can easily flick back and forth between participants without needing to close that modal window. Don’t spend too much time on this — you’re just trying to get a general impression of what happened.Keep an eye out for any card sorts that you might like to exclude from the results. For example participants who have lumped everything into one group and haven’t actually sorted the cards. Don’t worry - excluding or including participants isn’t permanent and can be toggled on or off at anytime.If you have a good number of responses, then the Participant Centric Analysis (PCA) tab (below) can be a good place to head next. It’s great for doing a quick comparison of the different high-level approaches participants took when grouping the cards.The PCA tab provides the most insight when you have lots of results data (30+ completed card sorts) and at least one of the suggested IAs has a high level of agreement among your participants (50% or more agree with at least one IA).

The PCA tab compares data from individual participants and surfaces the top three ways the cards were sorted. It also gives you some suggestions based on participant responses around what these categories could be called but try not to get too bogged down in those - you’re still just trying to gain an overall feel for the results at this stage.Now is also a good time to take a super quick peek at the Categories tab as it will also help you spot patterns and identify data that you’d like to dive deeper into a bit later on!Another really useful visualization tool offered by OptimalSort that will help you build that early, high-level picture of your results is the Similarity Matrix. This diagram helps you spot data clusters, or groups of cards that have been more frequently paired together by your participants, by surfacing them along the edge and shading them in dark blue. It also shows the proportion of times specific card pairings occurred during your study and displays the exact number on hover (below).

In the above screenshot example we can see three very clear clusters along the edge: ‘Ankle Boots’ to ‘Slippers’ is one cluster, ‘Socks’ to ‘Stockings & Hold Ups’ is the next and then we have ‘Scarves’ to ‘Sunglasses’. These clusters make it easy to spot the that cards that participants felt belonged together and also provides hard data around how many times that happened.Next up are the dendrograms. Dendrograms are also great for gaining an overall sense of how similar (or different) your participants’ card sorts were to each other. Found under the Dendrogram tab in the results section of the tool, the two dendrograms are generated by different algorithms and which one you use depends largely on how many participants you have.

If your study resulted in 30 or more completed card sorts, use the Actual Agreement Method (AAM) dendrogram and if your study had fewer than 30 completed card sorts, use the Best Merge Method (BMM) dendrogram.The AAM dendrogram (see below) shows only factual relationships between the cards and displays scores that precisely tell you that ‘X% of participants in this study agree with this exact grouping’.In the below example, the study shown had 34 completed card sorts and the AAM dendrogram shows that 77% of participants agreed that the cards highlighted in green belong together and a suggested name for that group is ‘Bling’. The tooltip surfaces one of the possible category names for this group and as demonstrated here it isn’t always the best or ‘recommended’ one. Take it with a grain of salt and be sure to thoroughly check the rest of your results before committing!

The BMM dendrogram (see below) is different to the AAM because it shows the percentage of participants that agree with parts of the grouping - it squeezes the data from smaller sample sizes and makes assumptions about larger clusters based on patterns in relationships between individual pairs.The AAM works best with larger sample sizes because it has more data to work with and doesn’t make assumptions while the BMM is more forgiving and seeks to fill in the gaps.The below screenshot was taken from an example study that had 7 completed card sorts and its BMM dendrogram shows that 50% of participants agreed that the cards highlighted in green down the left hand side belong to ‘Accessories, Bottoms, Tops’.

Drill down and cross-reference

Once you’ve gained a high level impression of the results, it’s time to dig deeper and unearth some solid insights that you can share with your stakeholders and back up your design decisions.Explore your open and hybrid card sort data in more detail by taking a closer look at the Categories tab. Open up each category and cross-reference to see if people were thinking along the same lines.Multiple participants may have created the same category label, but what lies beneath could be a very different story. It’s important to be thorough here because the next step is to start standardizing or chunking individual participant categories together to help you make sense of your results.In open and hybrid sorts, participants will be able to label their categories themselves. This means that you may identify a few categories with very similar labels or perhaps spelling errors or different formats. You can standardize your categories by merging similar categories together to turn them into one.OptimalSort makes this really easy to do - you pretty much just tick the boxes alongside each category name and then hit the ‘Standardize’ button up the top (see below). Don’t worry if you make a mistake or want to include or exclude groupings; you can unstandardize any of your categories anytime.

Once you’ve standardized a few categories, you’ll notice that the Agreement number may change. It tells you how many participants agreed with that grouping. An agreement number of 1.0 is equal to 100% meaning everyone agrees with everything in your newly standardized category while 0.6 means that 60% of your participants agree.Another number to watch for here is the number of participants who sorted a particular card into a category which will appear in the frequency column in dark blue in the right-hand column of the middle section of the below image.

From the above screenshot we can see that in this study, 18 of the 26 participant categories selected agree that ‘Cat Eye Sunglasses’ belongs under ‘Accessories’.Once you’ve standardized a few more categories you can head over to the Standardization Grid tab to review your data in more detail. In the below image we can see that 18 participants in this study felt that ‘Backpacks’ belong in a category named ‘Bags’ while 5 grouped them under ‘Accessories’. Probably safe to say the backpacks should join the other bags in this case.

So that’s a quick overview of how to interpret the results from your open or hybrid card sorts.Here's a link to Part 2 of this series where we talk about interpreting results from closed card sorts as well as next steps for applying these juicy insights to your IA design process.

Further reading

- Card Sorting 101 – Learn about the differences between open, closed and hybrid card sorts, and how to run your own using OptimalSort.

- Which comes first: card sorting or tree testing? – Tree testing and card sorting can give you insight into the way your users interact with your site, but which comes first?

- How to pick cards for card sorting – What should you put on your cards to get the best results from a card sort? Here are some guidelines.

Building a brand new experience for Reframer

Reframer is a qualitative research tool that was built to help teams capture and make sense of their research findings quickly and easily. For those of you who have been a long-standing Optimal Workshop customer, you may know that Reframer has been in beta for some time. In fact, it has been in beta for 2 whole years. Truth was that, while we’ve cheerfully responded to your feedback with a number of cool features and improvements, we had some grand plans up our sleeve. So, we took everything we learned and went back to drawing board with the goal to provide the best dang experience we can.We’ll soon be ready to launch Reframer out of beta and let it take its place proudly as a full time member of our suite of user research tools. However, in the spirit of continuous improvement, we want to give you all a chance to use it and give us feedback on the new experience so far.

First-time Reframer user?

Awesome! You’ll get to experience the newer version of Reframer with a fresh set of eyes. To enable Reframer, log in to your Optimal Workshop account. On your dashboard you’ll see a button to join the Reframer beta on your screen at right.

Used Reframer before?

Any new studies you create will automatically use the slick new version. Not quite ready to learn the new awesome? No worries you can toggle back and forth between the old version and the new in the top right corner of your screen.To learn about Reframer’s new look and features, watch the video or read the transcript below to hear more about these changes and why we made them.

When is Reframer actually coming out of beta?

This year. Stay tuned.

Video transcript:

We’re this close to having our qualitative research tool, Reframer, all set to release from beta.But we just couldn’t wait to share some of the changes we’ve got lined up. So, we’ve gone ahead and launched a fresh version of Reframer to give you a taste of what’s to come.These latest updates include a more streamlined workflow and a cleaner user interface, as well as laying the foundations for some exciting features in the coming months.So let’s take a look at the revamped Reframer.We’ve updated the study screen to help you get started and keep track of where your research is at.

- You now have an area for study objectives to keep your team on the same page

- And an area for reference links, to give you quick access to prototypes and other relevant documents

- Session information is now shown here too, so you can get an overview of all your participants at a glance

- And we’ve created a home for your tags with more guidance around how to use them, like example tags and groups to help you get started.

What’s the most important thing when observing a research session? Collecting insights of course! So we’ve simplified the capture experience to let you focus on taking great notes.

- You can choose to reveal your tags, so they’re at the ready, or hide them so you can save your tagging till later

- We’ve created a whole range of keyboard shortcuts to speed up adding and formatting observations

- The import experience is now more streamlined, so it’s easier to bring observations from other sources into Reframer

- And, with some huge improvements behind the scenes, Reframer is even faster, giving you a more seamless note taking experience.

Now for something totally new — introducing review mode. Here you can see your own observations, as well as those made by anyone else in your team. This makes it easy to tidy up and edit your data after your session is complete. You can filter, search and tag observations, so you’ll be ready to make sense of everything when you move to analysis.We’ve added more guidance throughout Reframer, so you’ll have the confidence you’re on the right track. New users will be up and running in no time with improved help and easy access to resources.You might notice a few changes to our UI as well, but it’s not just about looks.

- We’ve changed the font to make it easier to read on any screen size

- Our updated button colours to provide better contrast and hierarchy

- And we’ve switched our icons from fonts to images to make them more accessible to more users.

And that’s where we’re at.We've got a lot more exciting features to come, so why not jump in, give the new Reframer a try and tell us what you think!Send us your feedback and ideas at research@optimalworkshop.com and keep an eye out for more changes coming soon. Catch you later!

My journey running a design sprint

Recently, everyone in the design industry has been talking about design sprints. So, naturally, the team at Optimal Workshop wanted to see what all the fuss was about. I picked up a copy of The Sprint Book and suggested to the team that we try out the technique.

In order to keep momentum, we identified a current problem and decided to run the sprint only two weeks later. The short notice was a bit of a challenge, but in the end we made it work. Here’s a run down of how things went, what worked, what didn’t, and lessons learned.

A sprint is an intensive focused period of time to get a product or feature designed and tested with the goal of knowing whether or not the team should keep investing in the development of the idea. The idea needs to be either validated or not validated by the end of the sprint. In turn, this saves time and resource further down the track by being able to pivot early if the idea doesn’t float.

If you’re following The Sprint Book you might have a structured 5 day plan that looks likes this:

- Day 1 - Understand: Discover the business opportunity, the audience, the competition, the value proposition and define metrics of success.

- Day 2 - Diverge: Explore, develop and iterate creative ways of solving the problem, regardless of feasibility.

- Day 3 - Converge: Identify ideas that fit the next product cycle and explore them in further detail through storyboarding.

- Day 4 - Prototype: Design and prepare prototype(s) that can be tested with people.

- Day 5 - Test: User testing with the product's primary target audience.

When you’re running a design sprint, it’s important that you have the right people in the room. It’s all about focus and working fast; you need the right people around in order to do this and not have any blocks down the path. Team, stakeholder and expert buy-in is key — this is not a task just for a design team!After getting buy in and picking out the people who should be involved (developers, designers, product owner, customer success rep, marketing rep, user researcher), these were my next steps:

Pre-sprint

- Read the book

- Panic

- Send out invites

- Write the agenda

- Book a meeting room

- Organize food and coffee

- Get supplies (Post-its, paper, Sharpies, laptops, chargers, cameras)

The sprint

Due to scheduling issues we had to split the sprint over the end of the week and weekend. Sprint guidelines suggest you hold it over Monday to Friday — this is a nice block of time but we had to do Thursday to Thursday, with the weekend off in between, which in turn worked really well. We are all self confessed introverts and, to be honest, the thought of spending five solid days workshopping was daunting. At about two days in, we were exhausted and went away for the weekend and came back on Monday feeling sociable and recharged again and ready to examine the work we’d done in the first two days with fresh eyes.

Design sprint activities

During our sprint we completed a range of different activities but here’s a list of some that worked well for us. You can find out more information about how to run most of these over at The Sprint Book website or checkout some great resources over at Design Sprint Kit.

Lightning talks

We kicked off our sprint by having each person give a quick 5-minute talk on one of these topics in the list below. This gave us all an overview of the whole project and since we each had to present, we in turn became the expert in that area and engaged with the topic (rather than just listening to one person deliver all the information).

Our lightning talk topics included:

- Product history - where have we come from so the whole group has an understanding of who we are and why we’ve made the things we’ve made.

- Vision and business goals - (from the product owner or CEO) a look ahead not just of the tools we provide but where we want the business to go in the future.

- User feedback - what have users been saying so far about the idea we’ve chosen for our sprint. This information is collected by our User Research and Customer Success teams.

- Technical review - an overview of our tech and anything we should be aware of (or a look at possible available tech). This is a good chance to get an engineering lead in to share technical opportunities.

- Comparative research - what else is out there, how have other teams or products addressed this problem space?

Empathy exercise

I asked the sprinters to participate in an exercise so that we could gain empathy for those who are using our tools. The task was to pretend we were one of our customers who had to present a dendrogram to some of our team members who are not involved in product development or user research. In this frame of mind, we had to talk through how we might start to draw conclusions from the data presented to the stakeholders. We all gained more empathy for what it’s like to be a researcher trying to use the graphs in our tools to gain insights.

How Might We

In the beginning, it’s important to be open to all ideas. One way we did this was to phrase questions in the format: “How might we…” At this stage (day two) we weren’t trying to come up with solutions — we were trying to work out what problems there were to solve. ‘We’ is a reminder that this is a team effort, and ‘might’ reminds us that it’s just one suggestion that may or may not work (and that’s OK). These questions then get voted on and moved into a workshop for generating ideas (see Crazy 8s).Read a more detailed instructions on how to run a ‘How might we’ session on the Design Sprint Kit website.

Crazy 8s

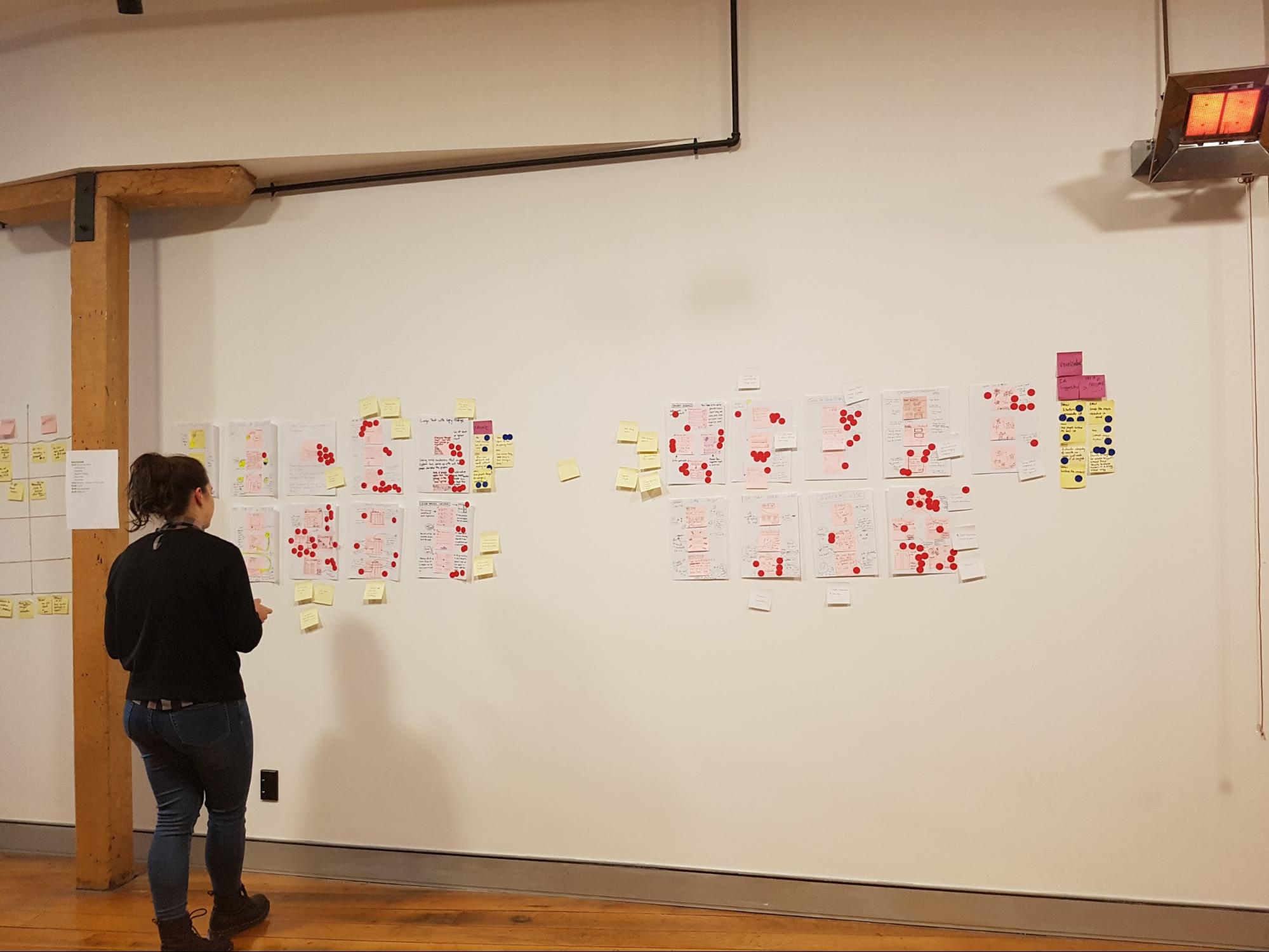

This activity is a super quick-fire idea generation technique. The gist of it is that each person gets a piece of paper that has been folded 8 times and has 8 minutes to come up with eight ideas (really rough sketches). When time is up, it’s all pens down and the rest of the team gets to review each other's ideas.In our sprint, we gave each person Post-it notes, paper, and set the timer for 8 minutes. At the end of the activity, we put all the sketches on a wall (this is where the art gallery exercise comes in).

Art gallery/Silent critique

The art gallery is the place where all the sketches go. We give everyone dot stickers so they can vote and pull out key ideas from each sketch. This is done silently, as the ideas should be understood without needing explanation from the person who made them. At the end of it you’ve got a kind of heat map, and you can see the ideas that stand out the most. After this first round of voting, the authors of the sketches get to talk through their ideas, then another round of voting begins.

Usability testing and validation

The key part of a design sprint is validation. For one of our sprints we had two parts of our concept that needed validating. To test one part we conducted simple user tests with other members of Optimal Workshop (the feature was an internal tool). For the second part we needed to validate whether we had the data to continue with this project, so we had our data scientist run some numbers and predictions for us.

Challenges and outcomes

One of our key team members, Rebecca, was working remotely during the sprint. To make things easier for her, we set up 2 cameras: one pointed to the whiteboard, the other was focused on the rest of the sprint team sitting at the table. Next to that, we set up a monitor so we could see Rebecca.

Engaging in workshop activities is a lot harder when working remotely. Rebecca would get around this by completing the activities and take photos to send to us.

Lessons

- Lightning talks are a great way to have each person contribute up front and feel invested in the process.

- Sprints are energy intensive. Make sure you’re in a good place with plenty of fresh air with comfortable chairs and a break out space. We like to split the five days up so that we get a weekend break.

- Give people plenty of notice to clear their schedules. Asking busy people to take five days from their schedule might not go down too well. Make sure they know why you’d like them there and what they should expect from the week. Send them an outline of the agenda. Ideally, have a chat in person and get them excited to be part of it.

- Invite the right people. It’s important that you get the right kind of people from different parts of the company involved in your sprint. The role they play in day-to-day work doesn’t matter too much for this. We’re all mainly using pens and paper and the more types of brains in the room the better. Looking back, what we really needed on our team was a customer support team member. They have the experience and knowledge about our customers that we don’t have.

- Choose the right sprint problem. The project we chose for our first sprint wasn’t really suited for a design sprint. We went in with a well defined problem and a suggested solution from the team instead of having a project that needed fresh ideas. This made the activities like ‘How Might We’ seem very redundant. The challenge we decided to tackle ended up being more of a data prototype (spreadsheets!). We used the week to validate assumptions around how we can better use data and how we can write a script to automate some internal processes. We got the prototype working and tested but due to the nature of the project we will have to run this experiment in the background for a few months before any building happens.

Overall, this design sprint was a great team bonding experience and we felt pleased with what we achieved in such a short amount of time. Naturally, here at Optimal Workshop, we're experimenters at heart and we will keep exploring new ways to work across teams and find a good middle ground.

Further reading

- The Sprint Book - a book by Jake Knapp

- Design Sprint Kit — a whole bunch of presentation decks, and activities for sprints

- Sprint Stories — some case studies that show the processes and value of design sprints

- How to run a remote design sprint without going crazy - an article by Jake Knapp

- Choosing the right sprint problem - a blog by Lisa Jansen

Arts, crafts and user feedback: How to engage your team through creative play

Doing research is one difficult task — sharing the results with your team is another. Reports can be skim read, forgotten and filed away. People can drift off into a daydream during slideshow presentations, and others may not understand what you’re trying to communicate.This is a problem that many research teams encounter, and it made me think a lot about how to make the wider team really engage in user feedback. While we at Optimal Workshop have a bunch of documents and great tools like Intercom, Evernote and Reframer to capture all our feedback, I wanted to figure out how I could make it fun and engaging to get people to read what our users tell us.How can we as designers and researchers better translate our findings into compelling insights and anecdotes for others to embrace and enjoy? After some thought and a trip to the craft store, I came up with this workshop activity that was a hit with the team.

Crafting feedback into art

Each fortnight we’ve been taking turns at running a full company activity instead of doing a full company standup (check in). Some of these activities included things like pairing up and going for a walk along the waterfront to talk about a challenge we are currently facing, or talk about a goal we each have. During my turn I came up with the idea of an arts and crafts session to get the team more engaged in reading some of our user feedback.Before the meeting, I asked every team member to bring one piece of user feedback that they found in Intercom, Evernote or Reframer. This feedback could be positive such as “Your customer support team is awesome” , a suggestion such as “It would be great to be able to hover over tags and see a tooltip with the description”, or it could be negative (opportunity) such as “I’m annoyed and confused with how recruitment works”.This meant that everyone in the team had to dig through the systems and tools we use and look for insights (nuggets) as their first task. This also helped the team gain appreciation for how much data and feedback our user researchers had been gathering.

After we all had one piece of feedback each I told everyone they get to spend the next half hour doing arts and crafts. They could use whatever they could find to create a poster, postcard, or visual interpretation of the insight they had.I provided colored card, emoji stickers, stencils, printed out memes, glitter and glue.During the next 30 minutes I stood back and saw everybody grinning and talking about their posters. The best thing was they were actually sharing their pieces of feedback with one another! We had everyone from devs, marketing, design, operations and finance all participating, which meant that people from all kinds of departments had a chance to read feedback from our customers.

At the end of the meeting we created a gallery in the office and we all spent time reading each poster because it was so fun to see what everyone came up with. We also hung up a few of these in spots around the office that get a lot of foot traffic, so that we can all have a reminder of some of the things our customers told us. I hope that each person took something away with them, and in the future, when working on a task they’ll remember back to a poster and think about how to tackle some of these requests!

How to run a creative play feedback workshop

Time needed: 30 minutesInsights: Print off a pile of customer insights or encourage the team to find and bring in their own. Have backups as some might be hard to turn into posters.Tools: Scissors, glue sticks, blue tack for creating the gallery.Crafts: Paper, pens, stickers, stencils, googly eyes (anything goes!)

Interested in other creative ways to tell stories? Our User Researcher Ania shares 8 creative ways to share your user research.If you do something similar in your team, we’d love to hear about it in the comments below!

Squirrel shoes, yoga and spacesuits: My experience at CanUX 2017

One of the great things about being in the UX field is the UX community. So many inspiring and generally all-round awesome people who are passionate about what they do. What happens when you get a big bunch of those fantastic people all in the one place? You can practically watch the enthusiasm and inspiration levels rise as people talk about ideas, experiences and challenges, and how they can help each other solve problems.Luckily for us, there are lots of events dedicated to getting UX people together in one place to share, learn, grow, and connect. CanUX is one of those, and I was fortunate enough to be there in Ottawa to speak at this year’s event.

CanUX is the annual big UX event for Canada. Started 8 years ago by volunteers who wanted to create an opportunity for the Canadian UX community to get together, it’s grown from a small event to a major conference with top speakers from around the world. Still run by two of the original volunteers, CanUX has kept its focus on community which comes through clearly in how it’s organized. From the day of the week and time of year it’s held, through to details such as a yoga class at the venue to kick off the second day of the conference, there are countless details, small and large, that encourage people to go along, to meet others, and to catch up with old friends from previous CanUX conferences.Aware that there are natural energy lulls in conferences, as people’s brains fill up with inspiration and knowledge, the CanUX team have a regular MC, Rob Woodbridge. This is a man who bounds across the stage, encourages (and actually gets!) audience participation, swears, cracks jokes, and generally seems to have a lot of fun while being the most effective MC I have ever encountered. (Naturally, he’s a bit controversial — some people love to hate him because of that unbridled enthusiasm. But either way, he sets the tone for passionate, engaging presentations!)

With all the attention to detail around the rest of the conference, it’s not surprising that the same care is shown to the conference programme. All of the main presenters are seen ahead of time by one of the organizers, and then invited to be at CanUX. A very small number of short presentation times are set aside for an open call for submissions, to help encourage newer speakers. Presentations are chosen to cover research, design and IA topics, with both practical and inspirational talks in each.The talks themselves were fantastic, covering everything from the challenges of designing spacesuits for NASA, tips for overcoming challenges of being the lone UX person in a company, to the future of robotics in services, and how to get design systems up and working in a large organization. Two of the themes that came through strongest for me this year were inclusivity and empathy — for all of the wonderfully diverse people in the world, and also for people we often forget to take the time to understand and empathize with: our peers and our colleagues.

I feel very privileged to have been able to be involved in a conference that was so full of passion and dedication to UX, and to share the stage with so many inspiring people. The topic for my presentation was a subset of the outcomes of qualitative research I have been doing into who UX people are; in particular, the different types of challenges we face depending on our roles, the type of team we are in, our experience level, and (if reasonably new to UX) where our UX knowledge comes from. My talk seemed to be well received (yay!) — although some of the enthusiasm may have been due to the shoes with squirrel heels I was wearing, which got a lot of attention!

Overall, CanUX was the best organized and most thoughtful conference I’ve ever attended. The passion that the volunteer organizers have for the UX field comes through clearly, and really helps build community. Here’s hoping I’m lucky enough to get back to Ottawa for another one!

5 ways to increase user research in your organization

Co-authored by Brandon Dorn, UX designer at Viget.As user experience designers, making sure that websites and tools are usable is a critical component of our work, and conducting user research enables us to assess whether we’re achieving that goal or not. Even if we want to incorporate research, however, certain constraints may stand in our way.

A few years ago, we realized that we were facing this issue at Viget, a digital design agency, and we decided to make an effort to prioritize user research. Almost two years ago, we shared initial thoughts on our progress in this blog post. We’ve continued to learn and grow as researchers since then and hope that what we’ve learned along the way can help your clients and coworkers understand the value of research and become better practitioners. Below are some of those lessons.

Make research a priority for your organization

Before you can do more research, it needs to be prioritized across your entire organization — not just within your design team. To that end, you should:

- Know what you’re trying to achieve. By defining specific goals, you can share a clear message with the broader organization about what you’re after, how you can achieve those goals, and how you will measure success. At Viget, we shared our research goals with everyone at the company. In addition, we talked to the business development and project management teams in more depth about specific ways that they could help us achieve our goals, since they have the greatest impact on our ability to do more research.

- Track your progress. Once you’ve made research a priority, make sure to review your goals on an ongoing basis to ensure that you’re making progress and share your findings with the organization. Six months after the research group at Viget started working on our goals, we held a retrospective to figure out what was working — and what wasn’t.

- Adjust your approach as needed. You won’t achieve your goals overnight. As you put different tactics into action, adjust your approach if something isn’t helping you achieve your goals. Be willing to experiment and don’t feel bad if a specific tactic isn’t successful.

Educate your colleagues and clients

If you want people within your organization to get excited about doing more research, they need to understand what research means. To educate your colleagues and clients, you should:

- Explain the fundamentals of research. If someone has not conducted research before, they may not be familiar or feel comfortable with the vernacular. Provide an overview of the fundamental terminology to establish a basic level of understanding. In a blog post, Speaking the Same Language About Research, we outline how we established a common vocabulary at Viget.

- Help others understand the landscape of research methods. As designers, we feel comfortable talking about different methodologies and forget that that information will be new to many people. Look for opportunities to increase understanding by sharing your knowledge. At Viget, we make this happen in several ways. Internally, we give presentations to the company, organize group viewing sessions for webinars about user research, and lead focused workshops to help people put new skills into practice. Externally, we talk about our services and share knowledge through our blog posts. We are even hosting a webinar about conducting user interviews in November and we'd love for you to join us.

- Incorporate others into the research process. Don't just tell people what research is and why it's important — show them. Look for opportunities to bring more people into the research process. Invite people to observe sessions so they can experience research firsthand or have them take on the role of the notetaker. Another simple way to make people feel involved is to share findings on an ongoing basis rather than providing a report at the end of the process.

Broaden your perspective while refining your skill set

Our commitment to testing assumptions led us to challenge ourselves to do research on every project. While we're dogmatic about this goal, we're decidedly un-dogmatic about the form our research takes from one project to another. To pursue this goal, we seek to:

- Expand our understanding. To instill a culture of research at Viget, we've found it necessary to question our assumptions about what research looks like. Books like Erika Hall’s Just Enough Research teach us the range of possible approaches for getting useful user input at any stage of a project, and at any scale. Reflect on any methodological biases that have become well-worn paths in your approach to research. Maybe your organization is meticulous about metrics and quantitative data, and could benefit from a series of qualitative studies. Maybe you have plenty of anecdotal and qualitative evidence about your product that could be better grounded in objective analysis. Aim to establish a balanced perspective on your product through a diverse set of research lenses, filling in gaps as you learn about new approaches.

- Adjust our approach to project constraints. We've found that the only way to consistently incorporate research in our work is to adjust our approach to the context and constraints of any given project. Client expectations, project type, business goals, timelines, budget, and access to participants all influence the type, frequency, and output of our research. Iterative prototype testing of an email editor, for example, looks very different than post-launch qualitative studies for an editorial website. While some projects are research-intensive, short studies can also be worthwhile.

- Reflect on successes and shortcomings. We have a longstanding practice of holding post-project team retrospectives to reflect on and document lessons for future work. Research has naturally come up in these conversations, and many of the things we've discussed you're reading right now. As an agency with a diverse set of clients, it's been important for us to understand what types of research work for what types of clients, and when. Make sure to take time to ask these questions after projects. Mid-project retrospectives can be beneficial, especially on long engagements, yet it's hard to see the forest when you're in the weeds.

Streamline qualitative research processes 🚄

Learning to be more efficient at planning, conducting, and analyzing research has helped us overturn the idea that some projects merit research while others don't. Remote moderated usability tests are one of our preferred methods, yet, in our experience, the biggest obstacle to incorporating these tests isn't the actual moderating or analyzing, but the overhead of acquiring and scheduling participants. While some agencies contract out the work of recruiting, we've found it less expensive and more reliable to collaborate with our clients to find the right people for our tests. That said, here are some recommendations for holding efficient qualitative tests:

- Know your tools ahead of time. We use a number of tools to plan, schedule, annotate, and analyze qualitative tests (we're inveterate spreadsheet users). Learn your tools beforehand, especially if you're trying something new. Tools should fade into the background during tests, which Reframer does nicely.

- Establish a recruiting process. When working with clients to find participants, we'll often provide an email template tailored to the project for them to send to existing or potential users of their product. This introductory email will contain a screener that asks a few project-related demographic or usage questions, and provides us with participant email addresses which we use to follow-up with a link to a scheduling tool. Once this process is established, the project manager will ensure that the UX designer on the team has a regular flow of participants. The recruiting process doesn't take care of itself – participants cancel, or reschedule, or sometimes don't respond at all – yet establishing an approach ahead of time allows you, the researcher, to focus on the research in the midst of the project.

- Start recruiting early. Don't wait until you've finished writing a testing script to begin recruiting participants. Once you determine the aim and focal points of your study, recruit accordingly. Scripts can be revised and approved in the meantime.

Be proactive about making research happen 🤸

As a generalist design agency, we work with clients whose industries and products vary significantly. While some clients come to us with clear research priorities in mind, others treat it as an afterthought. Rare, however, is the client who is actively opposed to researching their product. More often than not, budget and timelines are the limiting factors. So we try not to make research an ordeal, but instead treat it as part of our normal process even if a client hasn't explicitly asked for it. Common-sense perspectives like Jakob Nielsen’s classic “Discount Usability for the Web” remind us that some research is always better than none, and that some can still be meaningfully pursued. We aren’t pushy about research, of course, but instead try to find a way to make it happen when it isn't a definite priority.

World Usability Day is coming up on November 9, so now is a great time to stop and reflect on how you approach research and to brainstorm ways to improve your process. The tips above reflect some of the lessons we’ve learned at Viget as we’ve tried to improve our own process. We’d love to hear about approaches you’ve used as well.

No results found.