Optimal Blog

Articles and Podcasts on Customer Service, AI and Automation, Product, and more

In our Value of UX Research report, nearly 70% of participants identified analysis and synthesis as the area where AI could make the biggest impact.

At Optimal, we're all about cutting the busywork so you can spend more time on meaningful insights and action. That’s why we’ve built automated Insights, powered by AI, to instantly surface key themes from your survey responses.

No extra tools. No manual review. Just faster insights to help you make quicker, data-backed decisions.

What You’ll Get with Automated Insights

- Instant insight discovery

Spot patterns instantly across hundreds of responses without reading every single one. Get insights served up with zero manual digging or theme-hunting. - Insights grounded in real participant responses

We show the numbers behind every key takeaway, including percentage and participant count, so you know exactly what’s driving each insight. And when participants say it best, we pull out their quotes to bring the insights to life. - Zoom in for full context

Want to know more? Easily drill down to the exact participants behind each insight for open text responses, so you can verify, understand nuances, and make informed decisions with confidence. - Segment-specific insights

Apply any segment to your data and instantly uncover what matters most to that group. Whether you’re exploring by persona, demographic, or behavior, the themes adapt accordingly. - Available across the board

From survey questions to pre- and post-study, and post-task questions, you’ll automatically get Insights across all question types, including open text questions, matrix, ranking, and more.

Automate the Busywork, Focus on the Breakthroughs

Automated Insights are just one part of our ever-growing AI toolkit at Optimal. We're making it easier (and faster) to go from raw data to real impact, such as our AI Simplify tool to help you write better survey questions, effortlessly. Our AI assistant suggests clearer, more effective wording to help you engage participants and get higher-quality data.

Ready to level up your UX research? Log into your account to get started with these newest capabilities or sign up for a free trial to experience them for yourselves.

Topics

Research Methods

Popular

All topics

Latest

How to create a UX research plan

Summary: A detailed UX research plan helps you keep your overarching research goals in mind as you work through the logistics of a research project.

There’s nothing quite like the feeling of sitting down to interview one of your users, steering the conversation in interesting directions and taking note of valuable comments and insights. But, as every researcher knows, it’s also easy to get carried away. Sometimes, the very process of user research can be so engrossing that you forget the reason you’re there in the first place, or unexpected things that come up that can force you to change course or focus.

This is where a UX research plan comes into play. Taking the time to set up a detailed overview of your high-level research goals, team, budget and timeframe will give your research the best chance of succeeding. It's also a good tool for fostering alignment - it can make sure everyone working on the project is clear on the objectives and timeframes. Over the course of your project, you can refer back to your plan – a single source of truth. After all, as Benjamin Franklin famously said: “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail”.

In this article, we’re going to take a look at the best way to put together a research plan.

Your research recipe for success

Any project needs a plan to be successful, and user research is no different. As we pointed out above, a solid plan will help to keep you focused and on track during your research – something that can understandably become quite tricky as you dive further down the research rabbit hole, pursuing interesting conversations during user interviews and running usability tests. Thought of another way, it’s really about accountability. Even if your initial goal is something quite broad like “find out what’s wrong with our website”, it’s important to have a plan that will help you to identify when you’ve actually discovered what’s wrong.

So what does a UX research plan look like? It’s basically a document that outlines the where, why, who, how and what of your research project.

It’s time to create your research plan! Here’s everything you need to consider when putting this plan together.

Make a list of your stakeholders

The first thing you need to do is work out who the stakeholders are on your project. These are the people who have a stake in your research and stand to benefit from the results. In those instances where you’ve been directed to carry out a piece of research you’ll likely know who these people are, but sometimes it can be a little tricky. Stakeholders could be C-level executives, your customer support team, sales people or product teams. If you’re working in an agency or you’re freelancing, these could be your clients.

Make a list of everyone you think needs to be consulted and then start setting up catch-up sessions to get their input. Having a list of stakeholders also makes it easy to deliver insights back to these people at the end of your research project, as well as identify any possible avenues for further research. This also helps you identify who to involve in your research (not just report findings back to).

Action: Make a list of all of your stakeholders.

Write your research questions

Before we get into timeframes and budgets you first need to determine your research questions, also known as your research objectives. These are the ‘why’ of your research. Why are you carrying out this research? What do you hope to achieve by doing all of this work? Your objectives should be informed by discussions with your stakeholders, as well as any other previous learnings you can uncover. Think of past customer support discussions and sales conversations with potential customers.

Here are a few examples of basic research questions to get you thinking. These questions should be actionable and specific, like the examples we’ve listed here:

- “How do people currently use the wishlist feature on our website?”

- “How do our current customers go about tracking their orders?”

- “How do people make a decision on which power company to use?”

- “What actions do our customers take when they’re thinking about buying a new TV?”

A good research question should be actionable in the sense that you can identify a clear way to attempt to answer it, and specific in that you’ll know when you’ve found the answer you’re looking for. It's also important to keep in mind that your research questions are not the questions you ask during your research sessions - they should be broad enough that they allow you to formulate a list of tasks or questions to help understand the problem space.

Action: Create a list of possible research questions, then prioritize them after speaking with stakeholders.

What is your budget?

Your budget will play a role in how you conduct your research, and possibly the amount of data you're able to gather.

Having a large budget will give you flexibility. You’ll be able to attract large numbers of participants, either by running paid recruitment campaigns on social media or using a dedicated participant recruitment service. A larger budget helps you target more people, but also target more specific people through dedicated participant services as well as recruitment agencies.

Note that more money doesn't always equal better access to tools - e.g. if I work for a company that is super strict on security, I might not be able to use any tools at all. But it does make it easier to choose appropriate methods and that allow you to deliver quality insights. E.g. a big budget might allow you to travel, or do more in-person research which is otherwise quite expensive.

With a small budget, you’ll have to think carefully about how you’ll reward participants, as well as the number of participants you can test. You may also find that your budget limits the tools you can use for your testing. That said, you shouldn’t let your budget dictate your research. You just have to get creative!

Action: Work out what the budget is for your research project. It’s also good to map out several cheaper alternatives that you can pursue if required.

How long will your project take?

How long do you think your user research project will take? This is a necessary consideration, especially if you’ve got people who are expecting to see the results of your research. For example, your organization’s marketing team may be waiting for some of your exploratory research in order to build customer personas. Or, a product team may be waiting to see the results of your first-click test before developing a new signup page on your website.

It’s true that qualitative research often doesn’t have a clear end in the way that quantitative research does, for example as you identify new things to test and research. In this case, you may want to break up your research into different sub-projects and attach deadlines to each of them.

Action: Figure out how long your research project is likely to take. If you’re mixing qualitative and quantitative research, split your project timeframe into sub-projects to make assigning deadlines easier.

Understanding participant recruitment

Who you recruit for your research comes from your research questions. Who can best give you the answers you need? While you can often find participants by working with your customer support, sales and marketing teams, certain research questions may require you to look further afield.

The methods you use to carry out your research will also have a part to play in your participants, specifically in terms of the numbers required. For qualitative research methods like interviews and usability tests, you may find you’re able to gather enough useful data after speaking with 5 people. For quantitative methods like card sorts and tree tests, it’s best to have at least 30 participants. You can read more about participant numbers in this Nielsen Norman article.

At this stage of the research plan process, you’ll also want to write some screening questions. These are what you’ll use to identify potential participants by asking about their characteristics and experience.

Action: Define the participants you’ll need to include in your research project, and where you plan to source them. This may require going outside of your existing user base.

Which research methods will you use?

The research methods you use should be informed by your research questions. Some questions are best answered by quantitative research methods like surveys or A/B tests, with others by qualitative methods like contextual inquiries, user interviews and usability tests. You’ll also find that some questions are best answered by multiple methods, in what’s known as mixed methods research.

If you’re not sure which method to use, carefully consider your question. If we go back to one of our earlier research question examples: “How do our current customers go about tracking their orders?”, we’d want to test the navigation pathways.

If you’re not sure which method to use, it helps to carefully consider your research question. Let’s use one of our earlier examples: “Is it easy for users to check their order history in our iPhone app?” as en example. In this case, because we want to see how users move through our app, we need a method that’s suited to testing navigation pathways – like tree testing.

For the question: “What actions do our customers take when they’re thinking about buying a new TV?”, we’d want to take a different approach. Because this is more of an exploratory question, we’re probably best to carry out a round of user interviews and ask questions about their process for buying a TV.

Action: Before diving in and setting up a card sort, consider which method is best suited to answer your research question.

Develop your research protocol

A protocol is essentially a script for your user research. For the most part, it’s a list of the tasks and questions you want to cover in your in-person sessions. But, it doesn’t apply to all research types. For example, for a tree test, you might write your tasks, but this isn't really a script or protocol.

Writing your protocol should start with actually thinking about what these questions will be and getting feedback on them, as well as:

- The tasks you want your participants to do (usability testing)

- How much time you’ve set aside for the session

- A script or description that you can use for every session

- Your process for recording the interviews, including how you’ll look after participant data.

Action: This is essentially a research plan within a research plan – it’s what you’d take to every session.

Happy researching!

Related UX plan reading

- What is mixed methods research? – Learn how a mixture of qualitative and quantitative research methods can set your research project up for success.

- How to encourage people to participate in your study – Attracting participants to your study can be a tough undertaking. We’ve got a few different approaches to help.

- Which comes first: card sorting or tree testing? – Card sorting, tree testing, which one should you use first? And why does it matter?

- How to write great questions for your research – Learn how you can craft effective questions for your next research project.

- 5 ways to increase user research in your organization – One of the best ways to get other teams and stakeholders on board with your own research projects is by helping to spread awareness of the benefits of user research.

- How to lead a UX team – With user-centered design continuing to grow in organizations across the globe, we’re going to need skilled UX leaders.

- How to benchmark your information architecture – Before embarking on any major information architecture projects, learn how you can benchmark your existing one.

How to deal with the admin overhead of ResearchOps

One of the most common topics of conversation that I come across in research circles is how to deal with the administrative burden of user research. I see it time and again – both junior and experienced researchers alike struggling to balance delivering outputs for their stakeholders as well as actually managing the day-to-day of their jobs.

It’s not easy! Research is an admin-heavy field. All forms of user testing require a significant time investment for participant recruitment, user interviews mean sorting through notes in order to identify themes and different qualitative methods can leave you with pages of spreadsheet data. Staring down this potential mountain of administrative work is enough to make even the most seasoned researchers run for the hills.

Enter ResearchOps. Sprouting up in 2018, various researchers came together to try and standardize different research practices and processes in order to support researchers and streamline operations. It may seem like a silver bullet, but the fundamental questions still remain. How can you, as a researcher, manage the administrative side of your job? And where does your responsibility end and your colleagues’ begin? Well, it’s time to find out.

Putting ResearchOps into perspective

As we touched on in the introduction, ResearchOps is here and it’s here to stay. Like its cousin DesignOps, ResearchOps represents an earnest and combined effort on the part of the research community to really establish research practices and give researchers a kind-of backbone to support them. Carrying out effective user research is more important now than ever before, so it’s key that vetted practices and processes are in place to guide the growing community of researchers. ResearchOps can also be instrumental in helping us establish boundaries and lines of communication.

But, it’s important to frame ResearchOps. This new ‘practice’ won’t magically solve the administrative burden that comes along with doing research. In fact, it’s likely that simply by having access to clear processes and practices, many researchers will identify more opportunities to run their research practices more effectively, which in many cases will mean, yep, you guessed it, more administrative work. Interestingly, Kate Towsey (one of the ‘founders’ of ResearchOps), best summed this situation up by describing ResearchOps as an API – elements you can ‘plug’ into your own research practice.

In dealing with these issues, there are some key questions you need to ask yourself.

Who owns research in your organization?

If you speak to researchers from different organizations, you’ll quickly realize that no two research practices are run the same way. In some cases, research teams are very well established operations, with hundreds of researchers following clearly set out processes and procedures in a very structured way. On the opposite end of the spectrum, you’ve got the more haphazard research operations, where people (perhaps not even ‘researchers’ in the traditional sense) are using research methods. The varied way in which research practices operate means the question of ownership is often a difficult one to answer – but it’s important.

Before we get into some of the strategies you can use to reduce and manage the administrative side of user research, you need to get a clear picture of who owns research in your organization. A fuzzy understanding of ownership makes the task of establishing boundaries near-impossible.

Strategies to manage the administrative burden of Research

Research is an admin-intensive practice. There’s no getting around it. And, while it’s true that some tools can help you to reduce the day-to-day admin of your job (typically by making certain methods easier to execute), there’s still a fair amount of strategic thinking that you’ll need to do. In other words, it’s time to look at some strategies you can use to ensure you’re doing the job in the most efficient way.

1. Know where your job stops

Understand what your colleagues expect from you, and what your organization expects from you. Knowing where your job stops (and where the jobs of the other members of your team begin) is key to the smooth running of a research practice. We’re talking about you – we’ll get to how research as a practice interacts with other parts of the organization in the next section. If you’re one of 5 researchers in your organization, a lack of alignment will lead to duplication of work, missed opportunities, and, in many cases, more admin. This is a constant issue, and it’s not one that researchers alone deal with. Needing to scramble to set up a meeting because 2 teams realize they’re both working on the same project happens all too often, in every type of organization.

2. Establish clear boundaries

Research, as a practice, can touch nearly every area of an organization. This is both by design and necessity. Research is consultative, and requires input from a number of parts of an organization. If not managed carefully, operating your research without clear boundaries can mean you’re stuck with significant amounts of administrative work.

Think about a typical research project:

- You might start by meeting with stakeholders to discuss what questions they want answered, or problems they want solved.

- Then, you may engage other researchers on your team to solicit their opinions as to how to proceed.

- You might test your studies with staff before taking them “live” and testing them with your target users.

- Depending on the research, you may need to engage with your legal department to work through risk assessments, consent forms, risk and ethical issues.

- At the end of your project, you’ll probably need to take your research and store it somewhere, a task that will involve more data governance conversations.

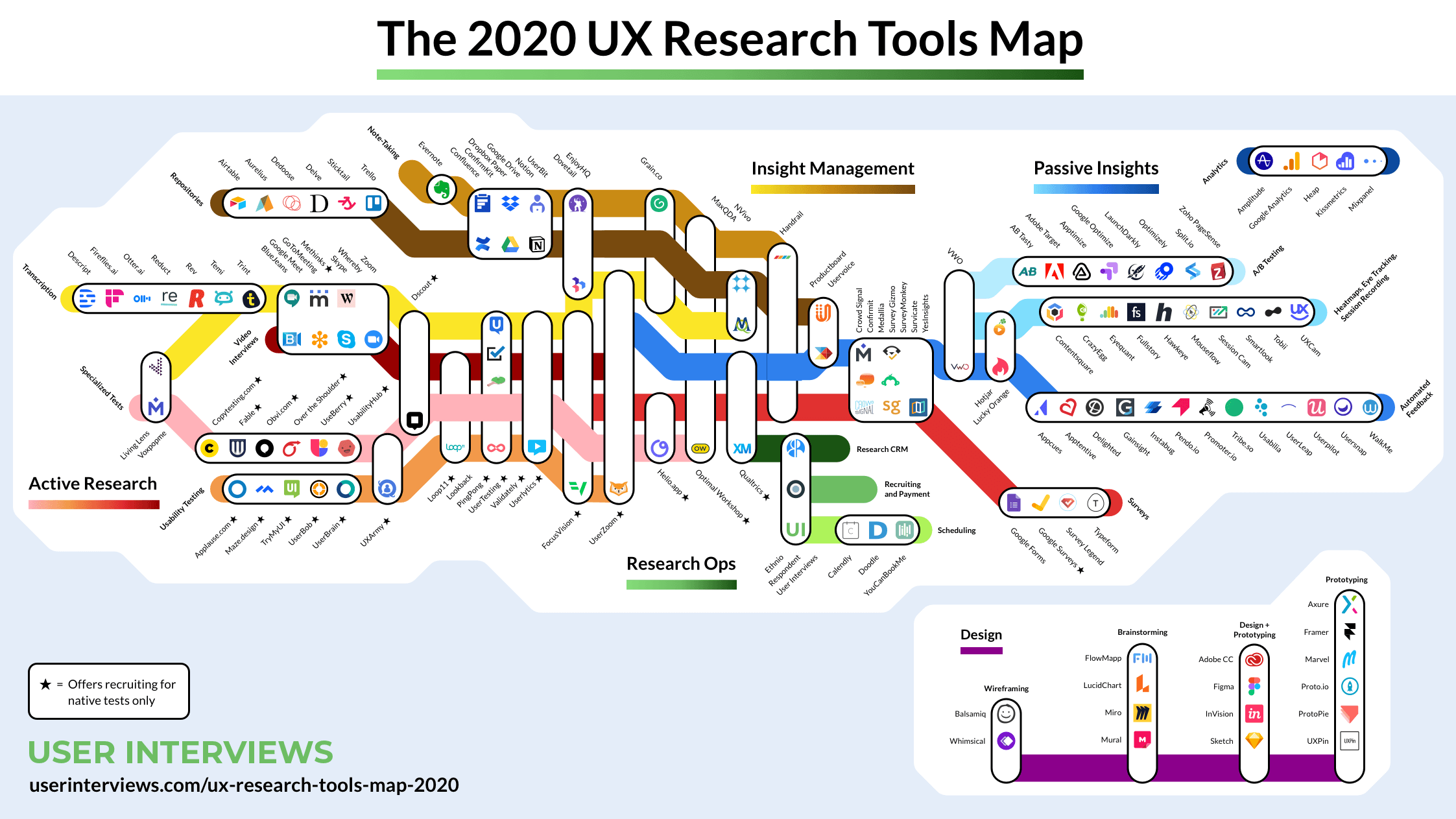

The ResearchOps community put together this fantastic framework (below) which maps out the majority of research processes.

“You can’t possibly handle any one bubble without touching many of the others, so it’s important to establish clear boundaries for what you, as research ops and as a person, cover,” Kate Towsey explains.

As for how to actually establish these boundaries – and in turn reduce the chance of an administrative overload – turn to conversations. One of the best ways to clear up any fogginess around remit is to simply pull the different parties into the same room and talk through your perspectives.

3. Outsource (if you need to)

In certain situations, it may make sense to outsource. Of course, we’re not talking about simply taking your research practice and outsourcing it wholesale, but instead taking select components that are well suited to being managed by third parties.

The obvious candidate here is participant recruitment. It’s typically one of the most time-consuming and admin-heavy parts of the research process, and coincidentally one that’s also easy to outsource. Participant recruitment services have access to tens of thousands of participants, and can pull together groups of participants for your research project, meaning you can eliminate the task of going out and searching for people manually. You simply specify the type of participant you require, and the service handles the rest.

Of course, there will always be times where manual participant recruitment is preferable, for example when you’re trying to recruit for user interviews for an extremely niche subject area, or you’re dealing with participants directly from your customer base.

4. Prioritize your research repository

Taking the time to establish a useful, usable repository of all of your research will be one of the best investments you can make as a researcher. There is a time commitment involved in setting up a research repository, but upsides are significant. For example, you’ll reduce admin as you’ll have a clear process for storing the insights from studies that you conduct. You’ll also find that when embarking on a new research project, you’ll have a good place to start. Instead of just blinding going out and starting from scratch, you can search through past studies in the repository to see if any similar research has been run in the past. That way, you can maximise the use of past research and focus on new research to get new insights.

What a good research repository looks like will depend on your organization’s needs to some extent, but there are some things to keep in mind:

- Your research should be easy to retrieve – There should be no barriers for researchers needing to access the research data.

- You should be able to trace insights back to the raw research data – If required, researchers should be able to trace the outputs of a research project back to the initial findings/raw data.

- It should be easy for others to access the findings from your research – Thinking beyond your cadre of user researchers, your repository should be fairly accessible to others in the organization. Marketers, designers and developers alike should be able to retrieve research when required.

- Sensitive data should be secure, or deleted if it’s not necessary – Your entire research repository should only be accessible to those within your organization, but you may need even tighter restrictions within that bubble. For example, you don’t want even the slightest chance of sensitive data leaking. By that same token, delete sensitive information when it’s not absolutely essential that you keep it.

Wrap-up

User research is always going to require a fair amount of administrative work, but there are actions you can take to minimize some of these more arduous and repetitive tasks – you just need to know where to start.

For more research strategy content, stay tuned to the Optimal Workshop Blog.

Happy testing!

New feature: Share pre- and post-questionnaire responses

We’ve just added the ability to share pre- and post-study questionnaire results directly from 4 of the Optimal Workshop tools. We’ve also introduced sharing to all questionnaire results in Questions. Read on to find out why we developed this feature and how it works.

Why we made this change

We want to make it as easy as possible for you to share the analysis outputs of your research with the people that need to see it. That’s why we’ve added some powerful new functionality to our UX tools.

Prior to this change, sharing questionnaire results could often be quite time-consuming. You’d need to download the results via the “Participant data” download, then transform them into a readable format and share them manually. Not ideal, and especially annoying when you’re in the midst of a project and just need to share the data quickly.

What we’ve changed

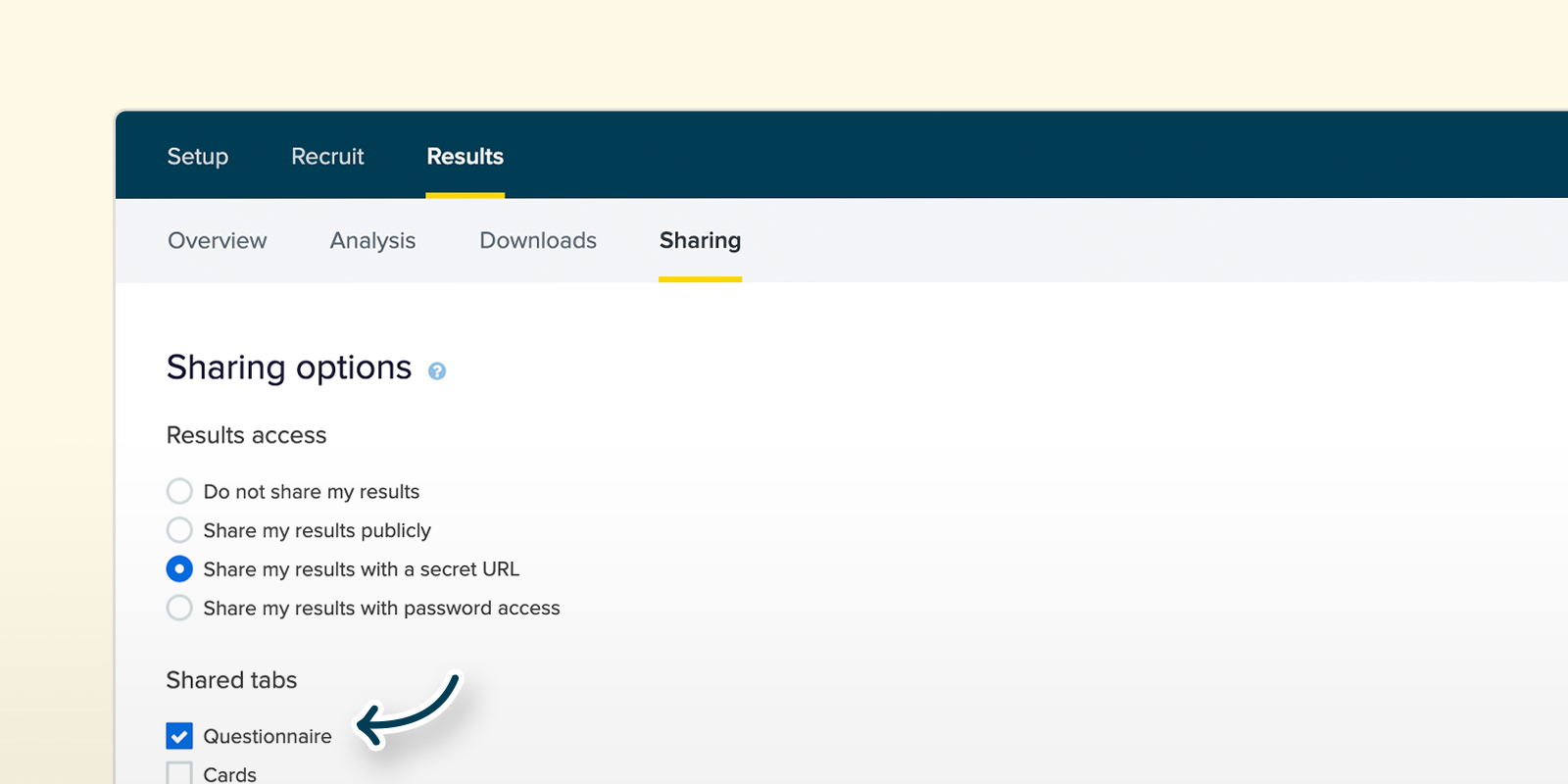

The existing “Sharing” tab (under “Results”) in OptimalSort, Treejack and Chalkmark will now have a “Questionnaire” tick box option under “Shared tabs”. Ticking this gives users the ability to share pre- and post-study questionnaire responses.

If you choose to share questionnaire results, keep in mind that you’re sharing raw responses from your participants. Before sharing with anyone, keep the privacy of your participants in mind and check if there’s any personally identifiable information included. If there is any personally identifiable information, you can always exclude the participant from your results on the “Participants” tab then go ahead and share your results.

Questions will get a new “Sharing” tab (under “Results”, it doesn’t currently have one) that will have one option (“Questionnaire”) that is always on and disabled.

The results page will behave much the same as it does currently, but now you’ll be able to see the individual participant responses for each question and share them.

What this means for you is that now, with the click of a button, you can share your questionnaire results with your team, stakeholders, clients and whoever else needs to see them. Easy!

Wrap up

We’ve got more exciting updates on the way for the tools in the Optimal Workshop platform – stay tuned to the newsfeed and our blog. You can also read about some of the other updates we’ve launched recently right here.

What is ResearchOps?

Back in early 2018, user researchers from around the globe got together to try and define an emerging practice – ResearchOps. The project eventually grew into a significant research effort called #WhatisResearchOps, involving 34 workshops, a survey that garnered over 300 responses and reams of analysis.

The goal was quite simple. Generate conversation around the work that researchers do in order to support them as research grows, with an eye toward standardizing common research practices. It’s an important undertaking: a report back carried out in 2017 found that 81 percent of executives agreed that user research made their organization more efficient. Further, 86 percent believed user research improved the quality of their products.

It’s clear that many organizations are starting to understand the value that user researchers bring to the table, it’s now up to the researchers to operationalize their practice.

But for the uninitiated, what exactly is ResearchOps? And why should you care?

What is ResearchOps?

To start off, there’s not a lot of literature about ResearchOps as of early 2020. Right now, it’s a practice that can certainly be classed as ‘emerging’. This is partly why we’re writing about it. We want to add our own kindling to the ResearchOps conversation fire.

ResearchOps as a practice has 2 main goals:

- Socialize research: Make it easier for the people in an organization to access the insights generated by user research, and allow them to actively take part in research activities.

- Operationalize research: Standardize templates, processes and plans to reduce research costs and the time required to get research projects off the ground.

Or, as Vidhya Sriram explains in the post we linked above, ResearchOps “democratizes customer insights, takes down barriers to understand customers, and makes everyone take responsibility for creating remarkable customer experiences.”

ResearchOps certainly hasn’t achieved anything close to ‘mainstream’ understanding yet, so in order to give ResearchOps the best chance of succeeding, it’s quite helpful to look at another ‘Ops’ practice – DesignOps.

As 2 ‘operations’ focused initiatives, DesignOps and ResearchOps share a lot of the same DNA. According to Nielsen Norman’s DesignOps 101 article, DesignOps “refers to the orchestration and optimization of people, processes, and craft in order to amplify design’s value and impact at scale”. Author Kate Kaplan goes on to flesh out this description, noting that it’s a term for addressing such issues as growing or evolving design teams, onboarding people with the right design skills, creating efficient workflows and improving design outputs. Sound familiar?

The world of DesignOps is a veritable smorgasbord of useful learnings for researchers looking to grow the practice of ResearchOps. One particularly useful element is the idea of selecting only the components of DesignOps that are relevant for the organization at that point in time. This is quite important. DesignOps is a broad topic, and there’s little sense in every organization trying to take on every aspect of it. The takeaway, DesignOps (and ResearchOps) should look very different depending on the organization.

Kate Kaplan also touches on another useful point in her Nielsen Norman Group article; the idea of the DesignOps menu:

This menu essentially outlines all of the elements that organizations could focus on when adopting practices to support designers. The DesignOps Menu is a useful framework for those trying to create a similar list of elements for ResearchOps.

Why does ResearchOps matter now?

It’s always been difficult to definitively say “this is the state of user research”. While some organizations intimately understand the value that a focus on customer centricity brings (and have teams devoted to the cause), others are years behind. In these lagging organizations, the researchers (or the people doing research), have to fight to prove the value of their work. This is one of the main reasons why ResearchOps as an initiative matters so much right now.

The other driver for ResearchOps is that the way researchers work together and with other disciplines is changing fast. In general, a growing awareness of the importance of the research is pushing the field together with data science, sales, customer support and marketing. All this to say, researchers are having to spend more and more time both proving the value of their work and operating at a more strategic level. This isn’t likely to slow, either. The coming years will see researchers spending less time doing actual research. With this in mind, ResearchOps becomes all the more valuable. By standardizing common research practices and working out ownership, the research itself doesn’t have to suffer.

What are the different components of ResearchOps?

As we touched on earlier, ResearchOps – like DesignOps – is quite a broad topic. This is necessary. As most practicing researchers know, there are a number of elements that go into ensuring thorough, consistent research.

A useful analogy for ResearchOps is a pizza. There are many different components (toppings) that can go on the pizza, which is reflected in how research exists in different organizations. The real point here is that no 2 research operations should look the same. Research at Facebook will look markedly different to research at a small local government agency in Europe.

We looked at the DesignOps Menu earlier as a model for ResearchOps, but there’s another, more specific map created as part of the #WhatisResearchOps project.

Like the DesignOps Menu, this map functions as a framework for what ResearchOps is. It’s the output of a series of workshops run by researchers across the globe as well as a large survey.

Who practices ResearchOps?

By now you should have a clear idea of the scale and scope of ResearchOps, given that we’ve covered the various components and why the practice matters so much. There are still 2 important topics left to cover, however: Who practices ResearchOps and (perhaps most interestingly) where it’s heading.

As the saying goes, “everyone’s a researcher”, and this certainly holds true when talking about ResearchOps, but here are some of the more specific roles that should be responsible for executing ResearchOps components.

- User researchers – Self-explanatory. The key drivers of research standardization and socialization.

- UX designers – Customer advocates to the core, UX designers follow user researchers quite closely when it comes to execution.

- Designers – Add to that, designers in general. As designers increasingly become involved in the research activities of their organizations, expect to see them having a growing stake in ResearchOps activities.

- Customer experience (CX) and marketing – Though they’re often not the foremost consideration when it comes to research conversations, marketing and CX certainly have a stake in research operations.

There’s also another approach that is worth considering: Research as a way of thinking. This can essentially be taken up by anyone, and it boils down to understanding the importance of a healthy research function, with processes, systems and tools in place to carry out research.

What’s next for ResearchOps?

As Kate Kaplan said in DesignOps 101, “DesignOps is the glue that holds the design organization together, and the bridge that enables collaboration among cross-disciplinary team members”. The same is true of ResearchOps – and it’s only going to become more important.

We’re going to echo the same call made by numerous other people helping to grow ResearchOps and say that if you’ve got some learnings to share, share them back with the community! We’re also always looking to share great UX and research content, so get in touch with us if you’ve got something to share on our blog.

Online card sorting: The comprehensive guide

When it comes to designing and testing in the world of information architecture, it’s hard to beat card sorting. As a usability testing method, card sorting is easy to set up, simple to recruit for and can supply you with a range of useful insights. But there’s a long-standing debate in the world of card sorting, and that’s whether it’s better to run card sorts in person (moderated) or remotely over the internet (unmoderated).

This article should give you some insight into the world of online card sorting. We've included an analysis of the benefits (and the downsides) as well as why people use this approach. Let's take a look!

How an online card sort works

Running a card sort remotely has quickly become a popular option just because of how time-intensive in-person card sorting is. Instead of needing to bring your participants in for dedicated card sorting sessions, you can simply set up your card sort using an online tool (like our very own OptimalSort) and then wait for the results to roll in.

So what’s involved in a typical online card sort? At a very high level, here’s what’s required. We’re going to assume you’re already set up with an online card sorting tool at this point.

- Define the cards: Depending on what you’re testing, add the items (cards) to your study. If you were testing the navigation menu of a hotel website, your cards might be things like “Home”, “Book a room”, “Our facilities” and “Contact us”.

- Work out whether to run a closed or open sort: Determine whether you’ll set the groups for participants to sort cards into (closed) or leave it up to them (open). You may also opt for a mix, where you create some categories but leave the option open for participants to create their own.

- Recruit your participants: Whether using a participant recruitment service or by recruiting through your own channels, send out invites to your online card sort.

- Wait for the data: Once you’ve sent out your invites, all that’s left to do is wait for the data to come in and then analyze the results.

That’s online card sorting in a nutshell – not entirely different from running a card sort in person. If you’re interested in learning about how to interpret your card sorting results, we’ve put together this article on open and hybrid card sorts and this one on closed card sorts.

Why is online card sorting so popular?

Online card sorting has a few distinct advantages over in-person card sorting that help to make it a popular option among information architects and user researchers. There are downsides too (as there are with any remote usability testing option), but we’ll get to those in a moment.

Where remote (unmoderated) card sorting excels:

- Time savings: Online card sorting is essentially ‘set and forget’, meaning you can set up the study, send out invites to your participants and then sit back and wait for the results to come in. In-person card sorting requires you to moderate each session and collate the data at the end.

- Easier for participants: It’s not often that researchers are on the other side of the table, but it’s important to consider the participant’s viewpoint. It’s much easier for someone to spend 15 minutes completing your online card sort in their own time instead of trekking across town to your office for an exercise that could take well over an hour.

- Cheaper: In a similar vein, online card sorting is much cheaper than in-person testing. While it’s true that you may still need to recruit participants, you won’t need to reimburse people for travel expenses.

- Analytics: Last but certainly not least, online card sorting tools (like OptimalSort) can take much of the analytical burden off you by transforming your data into actionable insights. Other tools will differ, but OptimalSort can generate a similarity matrix, dendrograms and a participant-centric analysis using your study data.

Where in-person (moderated) card sorting excels:

- Qualitative insights: For all intents and purposes, online card sorting is the most effective way to run a card sort. It’s cheaper, faster and easier for you. But, there’s one area where in-person card sorting excels, and that’s qualitative feedback. When you’re sitting directly across the table from your participant you’re far more likely to learn about the why as well as the what. You can ask participants directly why they grouped certain cards together.

Online card sorting: Participant numbers

So that’s online card sorting in a nutshell, as well as some of the reasons why you should actually use this method. But what about participant numbers? Well, there’s no one right answer, but the general rule is that you need more people than you’d typically bring in for a usability test.

This all comes down to the fact that card sorting is what’s known as a generative method, whereas usability testing is an evaluation method. Here’s a little breakdown of what we mean by these terms:

Generative method: There’s no design, and you need to get a sense of how people think about the problem you’re trying to solve. For example, how people would arrange the items that need to go into your website’s navigation. As Nielsen Norman Group explains: “There is great variability in different people's mental models and in the vocabulary they use to describe the same concepts. We must collect data from a fair number of users before we can achieve a stable picture of the users' preferred structure and determine how to accommodate differences among users”.

Evaluation method: There’s already a design, and you basically need to work out whether it’s a good fit for your users. Any major problems are likely to crop up even after testing 5 or so users. For example, you have a wireframe of your website and need to identify any major usability issues.

Basically, because you’ll typically be using card sorting to generate a new design or structure from nothing, you need to sample a larger number of people. If you were testing an existing website structure, you could get by with a smaller group.

Where to from here?

Following on from our discussion of generative versus evaluation methods, you’ve really got a choice of 2 paths from here if you’re in the midst of a project. For those developing new structures, the best course of action is likely to be a card sort. However, if you’ve got an existing structure that you need to test in order to usability problems and possible areas of improvement, you’re likely best to run a tree test. We’ve got some useful information on getting started with a tree test right here on the blog.

How to sell human-centered design

Picture this scenario: You're in your local coffee shop and hear a new song. You want to listen to it when you get back to the office. How do you obtain it? If you’re one of the 232 million Spotify users, you’ll simply open the app, search for the song and add it to your playlist. Within seconds, you’ll have the song ready to play whenever and wherever you want.

This new norm of music streaming wasn’t always the status quo. In the early days of the internet, the process of finding music was easy but nowhere nearly as easy as it is now. You’d often still be able to find any song you wanted, but you would need to purchase it individually or as part of an album, download it to your computer and then sync it across to a portable music player like the iPod.

Spotify is a prime example of successful human-centered design. The music service directly addresses the primary pain points with accessing music and building music collections by allowing users to pay a monthly fee and immediately gain access to a significant catalog of the world’s music.

It’s also far from the only example. Take HelloFresh, for example. Founded by Dominik Richter, Thomas Griesel and Jessica Nilsson in 2011, this company delivers a box of ingredients and recipes to your door each week, meaning there’s no need for grocery shopping or thinking about what to cook. It’s a service that addresses a fairly common problem: People struggle to find the time to go out and buy groceries and also create tasty, healthy meals, so the founders addressed both issues.

Both HelloFresh and Spotify are solutions to real user problems. They weren’t born as a result of people sitting in a black box and trying to come up with new products or services. This is the core of human-centered design – identifying something that people have trouble with and then building an appropriate answer.

The origins of human-centered design

But, someone is likely to ask, what’s even the point of human-centered design? Shouldn’t all products and services be designed for the people using them? Well, yes.

Interestingly, while terms like human-centered design and design thinking have become much more popular in recent years, they’re not entirely new methods of design. Designers have been doing this same work for decades, just under a different name: design. Just take one look at some of the products put together by famed industrial designer Dieter Rams (who famously influenced ex-Apple design lead Jony Ive). You can’t look at the product below and say it was designed without the end user in mind.

Why did human-centered design even gain traction as a term? David Howell (a UX designer from Australia) explains that designers often follow Parkinson’s Law, where “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion”. He notes that designers could always do more (more user research, more ideation, more testing, etc), and that by wrapping everything under a single umbrella (like human-centered design) designers can “speak to their counterparts in business as a process and elevate their standing, getting the coveted seat at the table”.

Human-centered design, for all intents and purposes, is really just a way for designers to package up the important principles intrinsic to good design and sell them to those who may not be sympathetic to exactly why they’re important. At a broader level, the same thinking can be applied to UX as a whole. Good user experience should naturally fall under design, but occasionally a different way of looking at something is necessary to drive the necessary progress.

So human-centered design can really just be thought of as a vehicle to sell the importance of a user-first approach to organizations – that’s useful, but how exactly are you supposed to start? How do you sell something that’s both easily understandable but at the same time quite nebulous? Well, you sell it in the same way you’d sell user research.

How to sell human-centered design

Focus on the product

In the simplest terms, a product designed and built based on user input is going to perform better than one that was assembled based on internal organizational thinking.

When utilized in the right way, taking a human-centered approach to product design leads to products that resonate much more effectively with people. We looked at Spotify at the beginning of this article for a company that’s continuously adopted this practice, but there are countless others. AirBnB, Uber, Pinterest and more all jump to mind. Google and LinkedIn, meanwhile, serve as good examples of the ‘old guard’ that are starting to invest more in the user experience.

Understand the cost-benefit

In 2013, Microsoft was set to unveil the latest version of its Xbox video game console. Up until that point, the company had found significant success in the videogame market. Past versions of the Xbox console had largely performed very well both critically and commercially. With the newest version, however, the company quickly ran into problems.

The new ‘Xbox One’ was announced with several features that attracted scorn from both the target market and the gaming press. The console would, for example, tie both physical and digital purchases to users’ accounts, meaning they wouldn’t be able to sell them on (a popular practice). The console would also need to remain connected to the internet to check these game licenses, likely leading to significant problems for those without reliable internet access. Lastly, Microsoft also stated that users would have to keep an included camera system plugged in at all times otherwise the console wouldn’t function. This led to privacy advocates arguing that the camera system’s data could be used for things like targeted advertising and user surveillance.

Needless to say, after seeing the response from the press and the console’s target market, Microsoft backtracked and eventually released the Xbox One without the always-on requirement, game licensing system or camera connection requirement.

Think of the costs Microsoft likely incurred having to roll back every one of these decisions so late into the product’s development. If you’re able to identify an issue in the research or prototype phase, it’s going to be significantly cheaper to fix here as opposed to 3 years into development with a release on the horizon.

Wrap-up

As the Spotify founders discovered back in back in 2008, taking a human-centered approach to product design can lead to revolutionary products and experiences. It’s not surprising. After all, how can you be expected to build something that people want to use without understanding said people?

No results found.