Getting stakeholders aligned and engaged with your research is rarely easy. In fact, it’s typically one of the hardest parts of being a user researcher.

I’ve seen it time and again: researchers pouring their hearts and souls into discovery and analysis projects, only to have leadership teams and different subject matter experts pay little or no attention to the outputs. There is one useful tool for stakeholder alignment, however, and when used correctly it can change how those aforementioned leadership teams and subject matter experts see your research.

Note-taking: A brief recap

The process of note-taking isn’t rocket science – and it’s exactly what it sounds like: Writing observations down during a user interview or other user test in order to identify any useful insights.

In more qualitative forms of research, the note-taking process is essential. It’s how you capture qualitative data. In a card sort, it’s more of an auxiliary exercise that can add another layer of insight.

The core skill with note-taking isn’t necessarily typing, it’s about the note-takers ability to transform observations that they’re making into readable and digestible text. Being a fast typer doesn’t always make for a good note-taker!

This is what makes note-taking an ideal tool for stakeholder engagement. It’s low effort and is an easy way to bring other people into the research process. This is time well spent, as the people who consume the outputs of your research should have an interest in the problems that you’re researching.

3 ways note-taking drives stakeholder engagement

Beyond being a tool to improve stakeholder engagement with your research, the added bonus of getting these people in the room with you as note-takers is that you’re free from the responsibility.

Whether it’s a card sort, user interview or usability test, you can focus on guiding your participants through the various tasks while your stakeholder jots down observations.

Here are 3 ways note-taking can help to drive stakeholder engagement in your research.

1. They get the chance to contribute to your research

Picture this. You’re at the end of your next research project, and you’re standing up at the front of a meeting room alongside a slide deck. It’s time to present your findings back to the original stakeholders of the project. Now consider how much more engaged they’ll be if they also had the opportunity to take part in the note-taking process.

Instead of simply reading your figures and findings, they’ll know exactly where they’ve come from and have a real connection to the data.

2. They can listen to real customers

It’s not often that stakeholders – typically those in leadership positions – get the chance to interact with customers. Usually, they hear about customer experiences second-hand from sales, marketing and customer service teams.

When you bring a stakeholder in as a note-taker, they’re able to hear from customers directly. Being in the room with customers as they try out new features or products is always interesting for those in the higher rungs of an organization.

3. You can generate insights together

Bringing stakeholders into your research sessions as note-takers means you can then collaborate with them to generate findings, thus helping you to reach a consensus quicker. Why does this work? Instead of simply taking a finalized set of findings to your stakeholders, they are with you in the room taking the notes and identifying insights together in the debrief session afterward.

The best tools for note-taking

Forget typing up notes in a document on a laptop – there are a significant number of qualitative note-taking tools available that make the process of note-taking and analysis much easier.

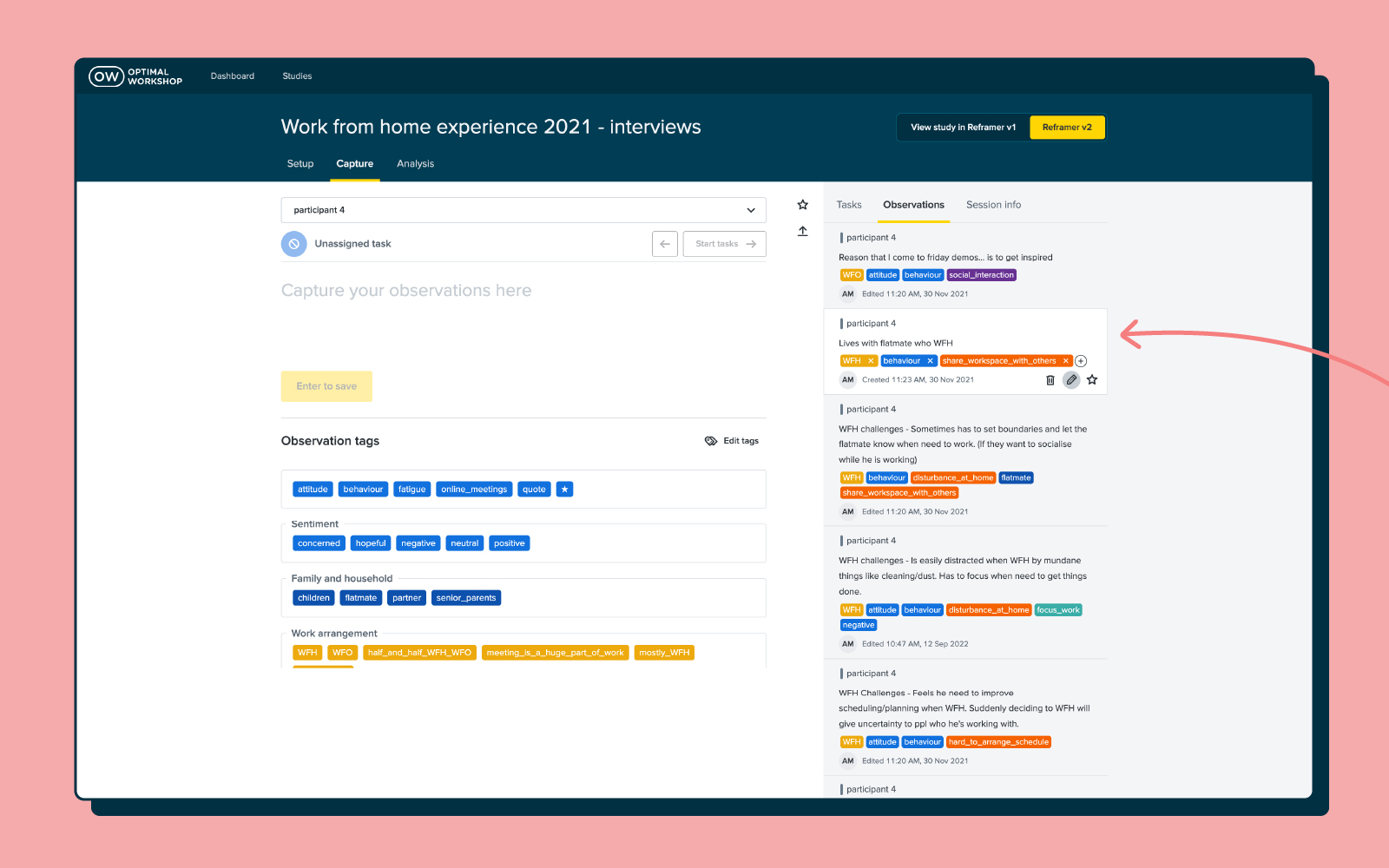

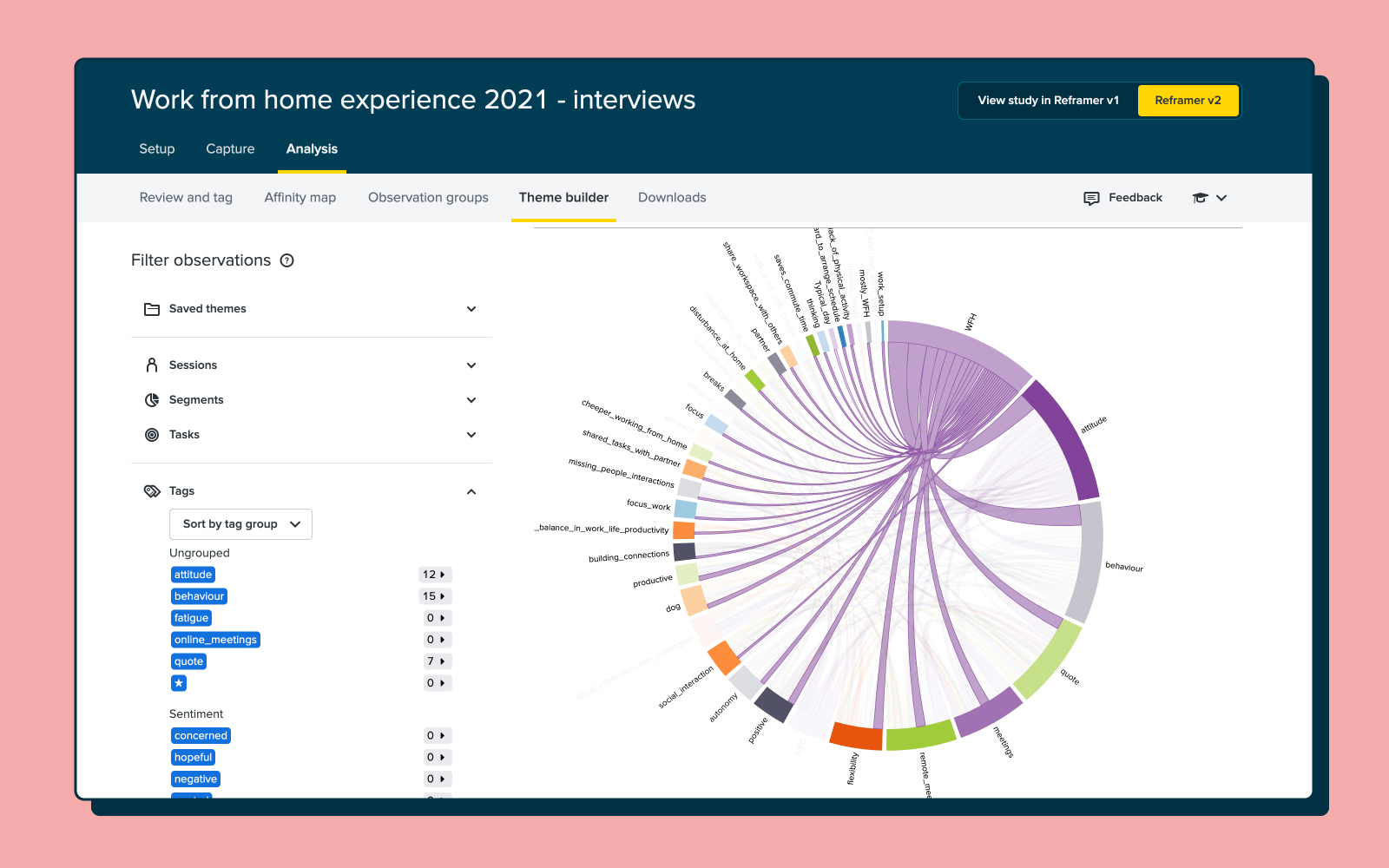

At Optimal Workshop, our tool for this job is Reframer, and it’s a powerful way to improve the qualitative note-taking process. With Reframer, you can log all your notes and observations in one place. After the research session is over, you can make sense of your findings quickly with easy-to-use analysis tools.

Wrap up

You don’t need to bring stakeholders in solely as note-takers. If they’d rather act as passive observers, there’s still immense value in having them in the room with you. Remember: It’s all about getting these people in sync with your research so that they’re better able to see the value of what you do, day to day!