Note: We’re gradually rolling out this feature, so it may not appear for you straight away.

We’ve made a few changes to our navigation header in-app to make it easier and more intuitive to use. In this blog post, we’ll explore the changes you’re going to see, why we made these changes and take a look at some of the testing that took place behind the scenes.

Let’s dive in!

What’s changed?

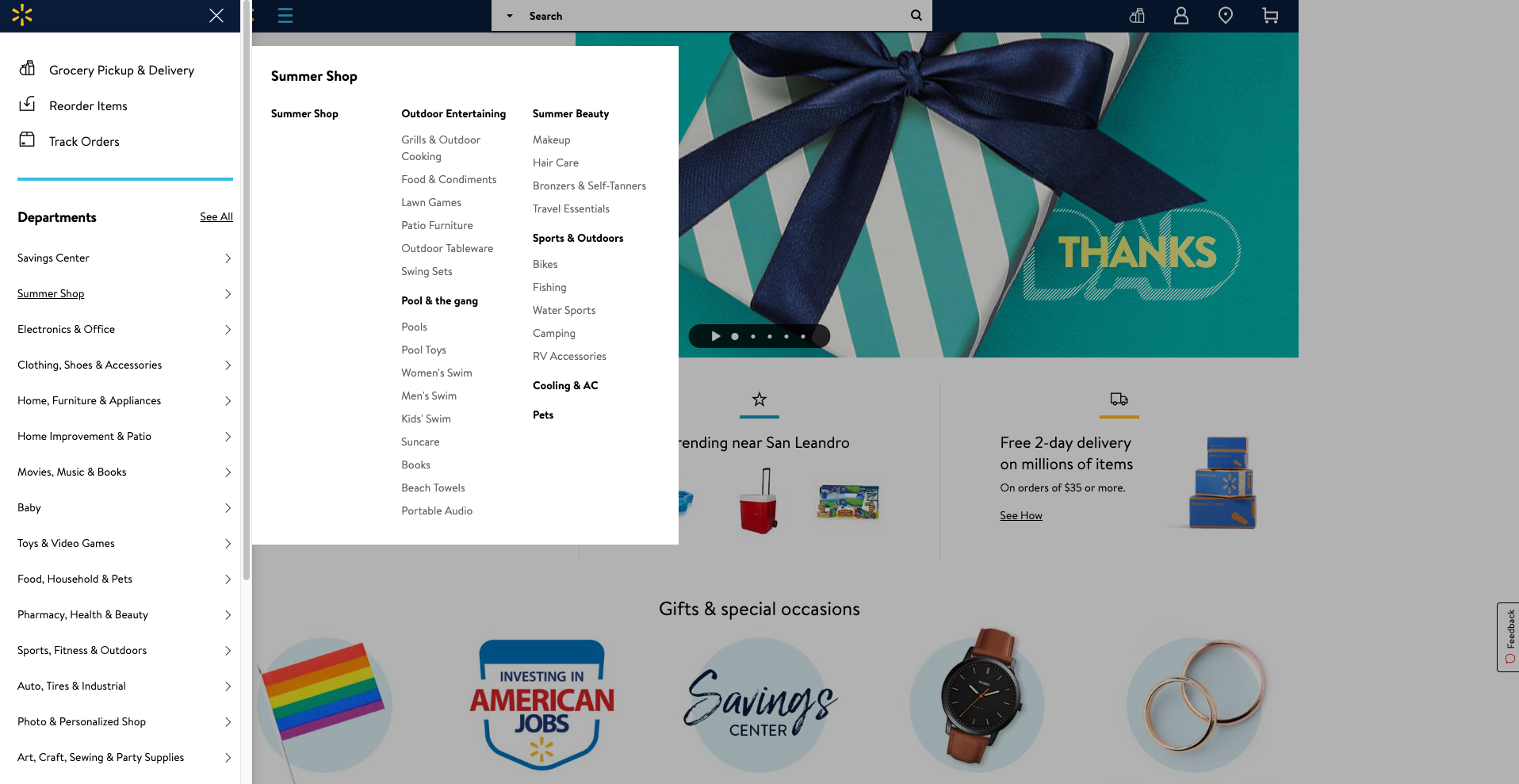

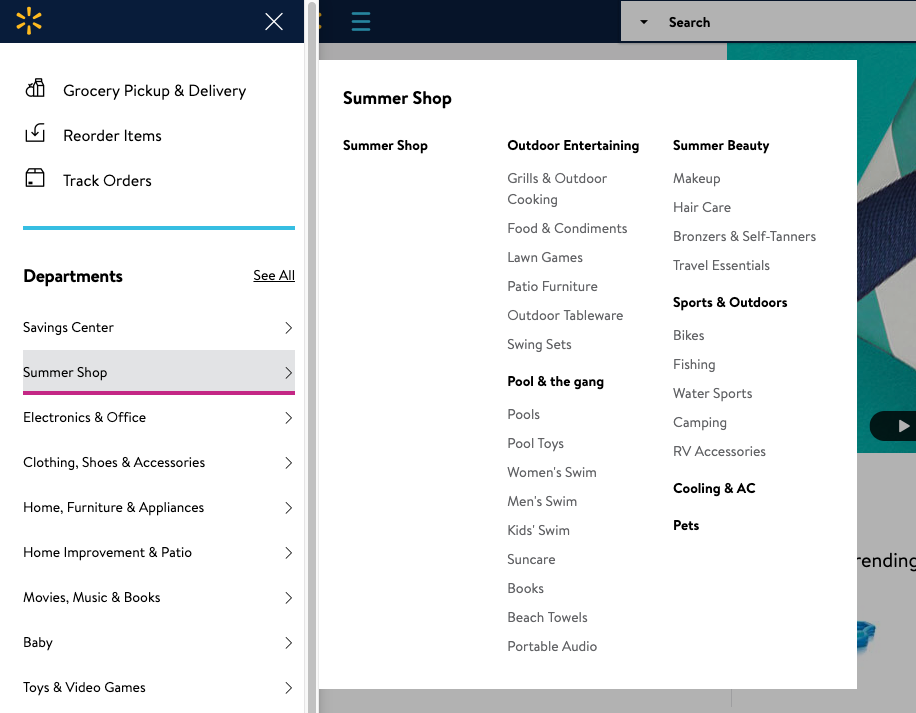

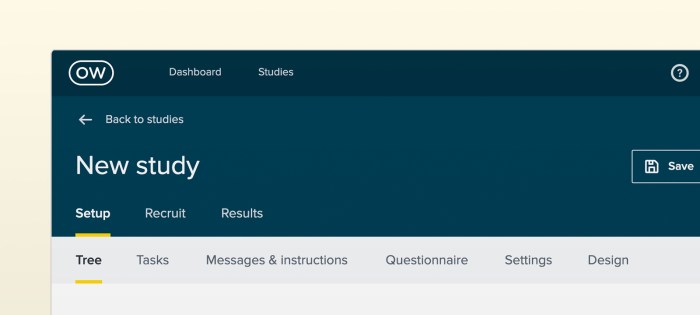

We’ve shuffled most tabs in the header around, but you’ll see the most obvious change when you create a study. You’ll now land directly on the ‘New Study’ screen, instead of being dropped in ‘Settings’ and then having to find your way to ‘Create Study’.

We’ve also made some changes to the ‘Create’, ‘Recruit’ and ‘Results’ tabs. These are now set in the header so you can easily navigate between creating, recruiting and reviewing results, instead of having to go back to ‘Settings’ to manage recruitment.

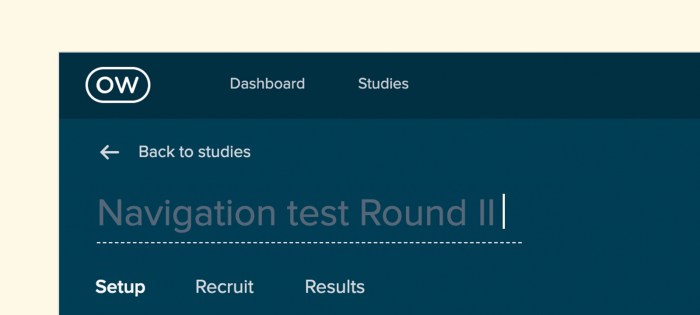

When you click ‘Back to studies’, you’ll now be taken back to the folder you’re currently working in. Previously you’d be taken back to the ‘All studies’ dashboard, so no more scrolling through the dashboard to find the folder you’re looking for. You can also rename your study in the header now, instead of having to navigate back to ‘Setup’.

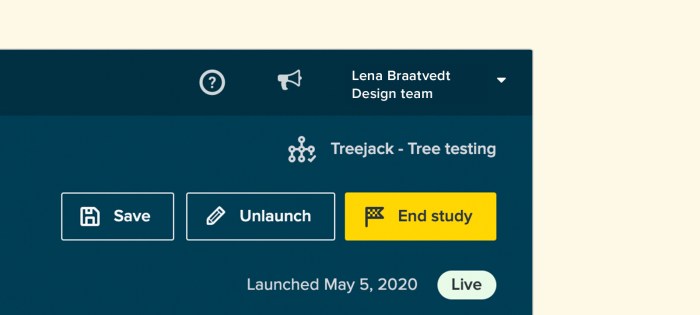

Finally, you can now end your study by clicking the ‘End study’ button in the header. We’d discovered that some people had trouble ending their studies in the past, now you can just click the button with the tiny checkered flag.

Why we made these changes

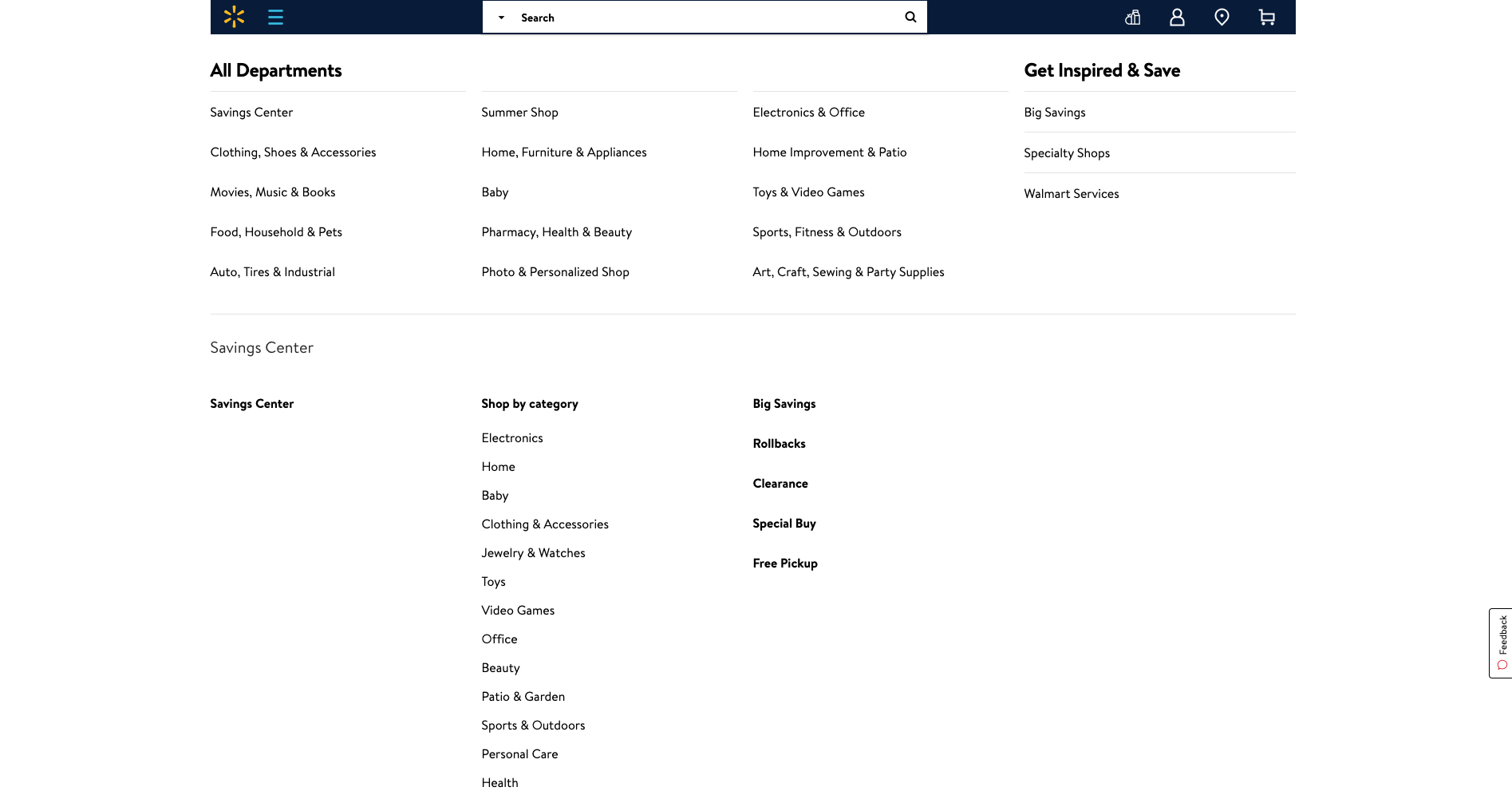

Our goal is to create the world’s best user research platform – and a big part of that is ensuring that our tools are easy to use. Through testing, we found that our old navigation header had usability, consistency and design issues. Specifically, usability testing and tree testing showed that simplifying our information architecture (IA) would drastically improve the user experience and flow.

We asked the question: “How might we improve the flow of our tool without affecting customers that currently use our tools?”

This led us down a research rabbit hole, but we came to the conclusion that we’d need to redesign the navigation header across all of our tools and adjust the IA to match the user journey. In other words, we needed to redesign the navigation to match how people were using our tools.

What we discovered during our user testing

User research and testing inform all of the changes that we make to our tools, and this project was no different.

We ran 3 tree tests using Treejack, testing 3 different IAs with 97 participants (30 per test). We also ran a first-click test using Chalkmark to validate what we were doing in Treejack.

The 3 IA’s we tested were:

- The same as the prototype (Create, Design, Launch, Recruit, Results)

- Removing Launch and splitting up children branches (Create, Design, Recruit, Results)

- Moving Design back into Create (Create, Recruit, Results)

Note: A caveat of the results is that we used the phrase ‘Set up’ in many questions which would bias the second test in favor of any question where ‘Setup’ is the correct answer.

We found that the third tree performed the best during our test. On average, it required a little less backtracking and was less direct than the first 2 tests, but had a higher chance of completion simply because there were fewer options available.

Wrap up

So that’s our new in-app header navigation – we hope you like it. Got a question? Feedback? Click the yellow Intercom circle in the bottom right-hand corner to get in touch with our support team.

Happy testing!