Optimal Blog

Articles and Podcasts on Customer Service, AI and Automation, Product, and more

At Optimal, we know the reality of user research: you've just wrapped up a fantastic interview session, your head is buzzing with insights, and then... you're staring at hours of video footage that somehow needs to become actionable recommendations for your team.

User interviews and usability sessions are treasure troves of insight, but the reality is reviewing hours of raw footage can be time-consuming, tedious, and easy to overlook important details. Too often, valuable user stories never make it past the recording stage.

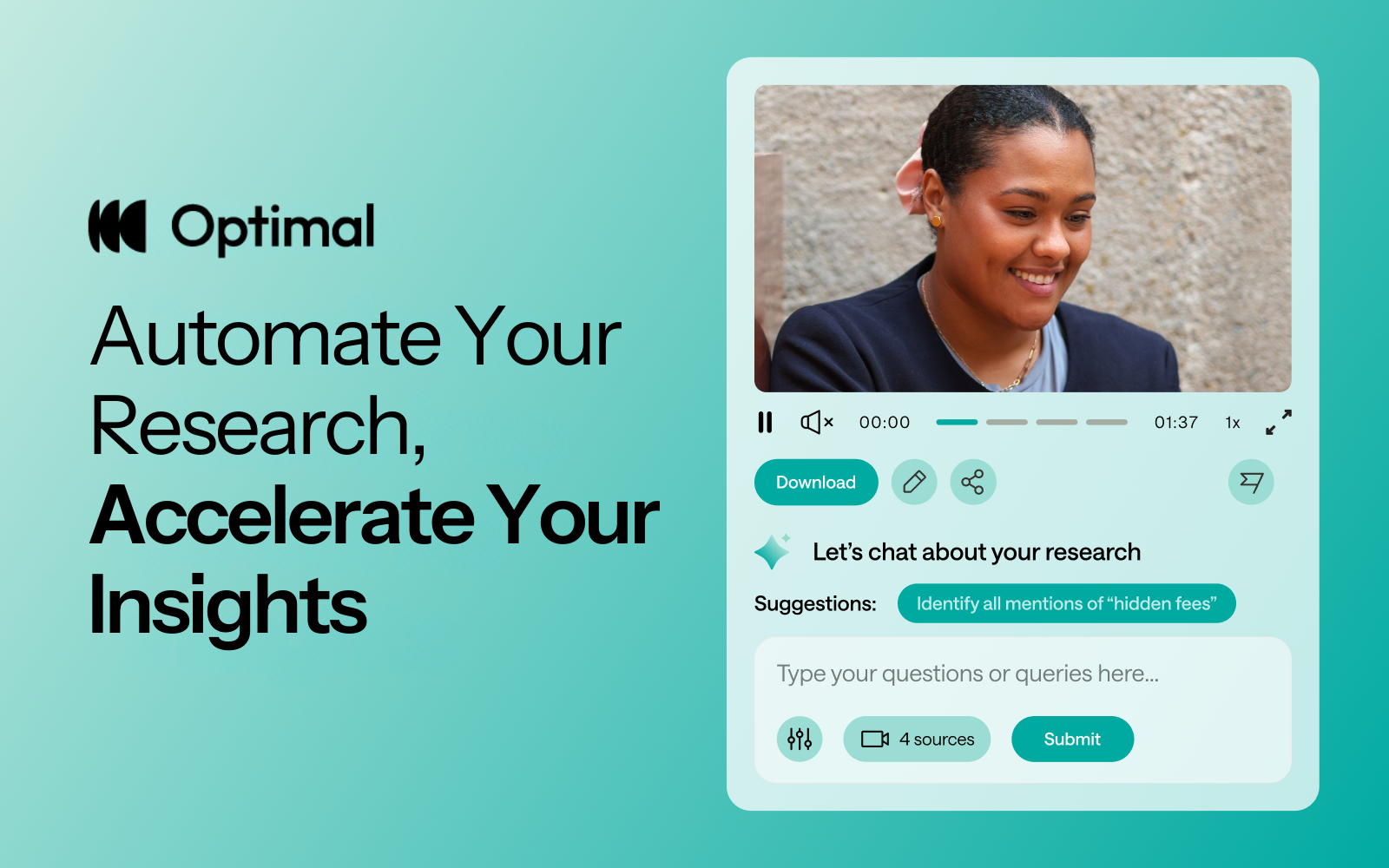

That's why we’re excited to announce the launch of early access for Interviews, a brand-new tool that saves you time with AI and automation, turns real user moments into actionable recommendations, and provides the evidence you need to shape decisions, bring stakeholders on board, and inspire action.

Interviews, Reimagined

What once took hours of video review now takes minutes. With Interviews, you get:

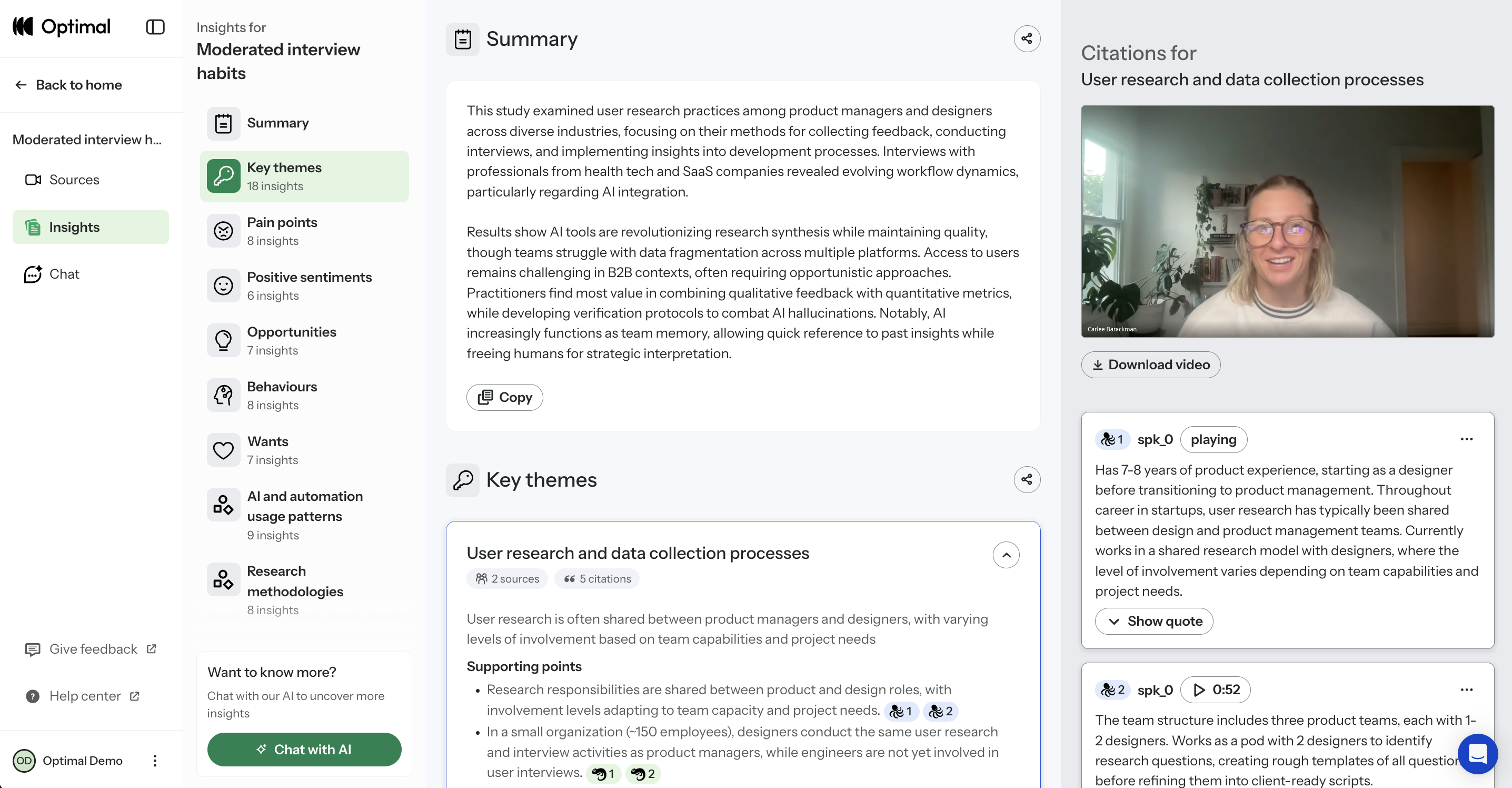

- Instant clarity: Upload your interviews and let AI automatically surface key themes, pain points, opportunities, and other key insights.

- Deeper exploration: Ask follow-up questions and anything with AI chat. Every insight comes with supporting video evidence, so you can back up recommendations with real user feedback.

- Automatic highlight reels: Generate clips and compilations that spotlight the takeaways that matter.

- Real user voices: Turn insight into impact with user feedback clips and videos. Share insights and download clips to drive product and stakeholder decisions.

Groundbreaking AI at Your Service

This tool is powered by AI designed for researchers, product owners, and designers. This isn’t just transcription or summarization, it’s intelligence tailored to surface the insights that matter most. It’s like having a personal AI research assistant, accelerating analysis and automating your workflow without compromising quality. No more endless footage scrolling.

The AI used for Interviews as well as all other AI with Optimal is backed by AWS Amazon Bedrock, ensuring that your AI insights are supported with industry-leading protection and compliance.

What’s Next: The Future of Moderated Interviews in Optimal

This new tool is just the beginning. Soon, you’ll be able to manage the entire moderated interview process inside Optimal, from recruitment to scheduling to analysis and sharing.

Here’s what’s coming:

- Recruit users using Optimal’s managed recruitment services.

- View your scheduled sessions directly within Optimal. Link up with your own calendar.

- Connect seamlessly with Zoom, Google Meet, or Teams.

Imagine running your full end-to-end interview workflow, all in one platform. That’s where we’re heading, and Interviews is our first step.

Ready to Explore?

Interviews is available now for our latest Optimal plans with study limits. Start transforming your footage into minutes of clarity and bring your users’ voices to the center of every decision. We can’t wait to see what you uncover.

Want to learn more and see it in action? Join us for our upcoming webinar on Oct 21st at 12 PM PST.

Topics

Research Methods

Popular

All topics

Latest

Dump trucks, explosives, and service design. A story about my UX career

Prelude

- A Blog: I’ve been asked to write one by Optimal Workshop. Exciting. Intimidating. Although I’m unsure exactly what they are – I’m yet to read any so I’d better try to – blogs push to the front of the hectic, clamouring queue in my head.

- Podcast: Everyone talks about them. They were lined up in about tenth position in the brain so hadn’t been seen to yet.

- Computer dyslexia: Is this a thing? Yes, indeed – I’m calling it! Even if I can’t find anything about it on Google. What appears so easy to others working with technology is such a struggle in my brain. Others find it all logical and cruisey, but me – I’m in a constant state of interface rage, and I just want it to make sense and stay in my brain until the next time I need it.

So I’m finally on a quick family holiday after a crazy few weeks following the wonderfully busy UX Australia conference. There are six of us in a one-bedroom apartment. It’s great … really! :-)I head to the gym to try the podcasting thing for the first time while doing a much-needed workout. It can’t be that hard.I fumble onto Dr Karl, then try “service design”, my interest area. I think I have pressed the right podcast but an entirely different one comes on. Is that my fault, or is there a mysterious trick to it all?It sounds good anyway and it’s about service design, a recount from a previous UX Australia presentation. I fail to catch the speaker's name but they are talking about the basics of service design so it will do nicely. I’m enjoying this while jogging (well, flailing, to be fair) and watching a poor elderly couple struggle over and over to enter the pool area. The card swipe that they use opens a door far away with no sounds or lights to indicate the way; there’s just a tiny insignificant sign. I had also struggled with this. With a sense of amusement – maybe irony – I’m listening to a podcast on service design while watching very poor service design in action and aching to design it better. I’m thinking of how I might write about this episode in my blog thingo when I catch who the speaker is. It’s Optimal Workshop. The very people who I’m writing the blog for. Beautiful.

My journey to becoming a UX Designer

I’m a UX designer. Sometimes I feel a bit fraudulent saying this. I try not to think that, but I do. I accidentally fell into the world of UX design, but it’s where I’m meant to be. I’m so pleased I found my home and my people. Finally, my weird way of thinking has a place and a name I can apply with some tentative authority these days … I am a UX designer. It’s getting easier to say.Born to immigrant parents in the 1970s, I ran away at 14 and barely made it through my High School Certificate, surviving only by training racehorses part time and skipping school to work on building sites for some very much needed cash in hand. I met an alcoholic and three beautiful daughters quickly arrived.In 2004, while travelling Australia like random gypsies in an old bus with a cute face, I suffered an accidental, medically induced heart attack and became really sick. My little heart was failing and I was told I would likely die. The girls were flown to stay with family and saying goodbye was the hardest thing I have ever done. They were so little.Clearly I didn’t die, but it was a slow and tough recovery.During this time, an opportunity to move to remote Groote Eylandt to live with the Anindilyakwan tribe in Angurugu came up, and of course we went. Family and friends said I was mad. There was little medical help available for my heart, and it was a very long way from a hospital.While living there, the local Manganese Mine decided to try using some local women to drive dump trucks. I was one of four chosen, so off I went to drive a two-story house on slippery mud. Magnificent fun!Driving dump trucks was awesome and I really enjoyed mining, but then I saw the blast crew and it looked like far more fun. I would ask Knuckles every day if I could go on blast crew. “Girls don’t do blast crew” was his constant response. I kept asking anyway. One day I said, “Knuckles, I will double your productivity as I will work twice as hard as the boys – and they can’t have a girl beat them, so your productivity will go up.” He swore, gave me a resigned look, and a one-week trial. And I was on blast crew.They were the best bunch of guys I ever had the joy of working with – such gentlemen – and I discovered I loved the adrenaline of blowing things up in the heat, humidity, mud, and storms.We left Groote in 2007, travelling in the cute bus again, and landed in Queensland’s Bowen Basin. I started blasting coal, but this was quite different to Groote Eylandt and I learned quickly that women are not always welcome on a mine site. Regardless of the enormous challenges, including death threats, I stuck it out. In fact, every challenge made me more determined than ever to excel in the industry.At the height of the global financial crisis, I found myself suddenly single with three girls to raise alone. The alcoholic had run off with another victim while I was working away on-site.I lost my job in the same week due to site shutdowns, and went to have my long hair sorted out. Sadly, due to a hairdresser’s accident, I lost all of my hair, too. It was a bad week as far as first-world problems go. In hindsight, though, it was a great week.Jobs were really scarce, but there was one going as an explosives operator in the Hunter Valley. I applied and was successful, so the girls and I packed up our meagre belongings and moved. I was the only female explosives operator working in the Valley then, and one of a handful in Australia – a highly male-dominated industry.It was a fairly tough time. Single mum, three daughters, shift work, and up to four hours of travel a day for work. I was utterly exhausted. Add to this an angry 14-year-old teenager who was doing everything to rebel against the world at the time. Much as her mum did at the same age.I found a local woman who was happy to live rent-free in exchange for part-time nannying while I worked shift work. This worked for a while but the teenagers were difficult, and challenged her authority. Needless to say, she didn’t last long term.

User Experience came driving around the corner

There was a job going with a local R&D department driving prototype explosives trucks. I submitted my little handwritten application. “Can you use a computer and Windows?” they asked. “Of course,” I said. But I couldn’t really.A few months later I had the job. It was closer to home, and only a little shift work was required.This was the golden ticket job I had been striving for. I was incredibly nervous about starting, but the night before I was woken at 11.00 pm by my 14-year-old daughter. She had tried to commit suicide by taking an overdose. I rushed her to hospital and stayed with her most of the night. Fortunately, she had not quite taken enough to cause the slow, painful, and unstoppable death, coming up four pills short. Heavily medicated, she was transferred to a troubled adolescents ward under lock and key. Unable to stay with my daughter, I turned up to my new job, exhausted and still in shock with a fake smile on my face. No one knew the ordeal.Learning how to navigate a computer at nearly 40 years of age was particularly challenging. I tried watching others, but it was not intuitive and I learned the frustration of interface rage early, almost constantly. I have computer dyslexia, for sure.Explosives operators are often like me – not very tech savvy. Some are very clever with computers, and some struggle to use a mobile phone and avoid owning a computer at all. In some countries, explosives operators are also illiterate.The job of delivering explosives is very particular. The trucks have many pumps, augers, and systems to manufacture complicated explosives mixtures accurately, utilising multiple raw materials stored in tanks on board. The management of this information is in the hands of operators who are brave, wonderfully intelligent, and hard-working people in general. Looking at a screen for up to 12 hours a day managing explosives mixtures can be frustrating if it’s set up ineffectively. Add to that new regulations and business requirements, making the job ever more complicated.I saw the new control system being created and thought the screens could be greatly improved from an operator’s perspective. I came up with an idea and designed a whole new system – very simplified, logical, and easy for the operators to use, if complicated in the back end. To be fair, at this point I had no idea about the “back end”. It was a mystical world of code the developers talked about in dark rooms.The screens now displayed only what the operator had to see at any time rather than the full suite of buttons and controls. The interface tidied right up – and with the addition of many new features that operators could turn on or off as they chose – the result was a simple, effective system that could be personalized to suit a style of loading. It was easy to manipulate to suit the changing conditions of bench loading, which requires total flexibility while offering tight control on safety, product quality, and opportunity of change.The problem was the magical choreography of the screens were dancing around in my head only; most people weren’t interested in my crazy drawings on butchers paper. I was thrown out of offices until someone finally listened to my rantings and my ideas were created as prototypes. These worked well enough to convince the business to develop the concept.A new project manager was hired to oversee the work. The less said about this person, the better, but it took a year before he was fired, and it was one of the toughest years I had to endure.In designing and developing concepts, I was actually following UX principles without knowing what they were. My main drive was to make the system consistent, logical, easy to understand at a glance, and able to capture effective data.I designed the system so as to allow the user to choose how they wanted to use the features; however, the best way was also the easiest way. I hate bossy software – being forced into corners and feeling the interface rage while just trying to do your job. It’s unacceptable.Designing interfaces and control systems is what I love to do, and I have now designed or contributed to designing four systems. I love the ability to change the way a person will perform a job just by implementing a simple alteration in software that changes the future completely. Making software suit the audience rather than the audience suit the software while achieving business goals – I love it.Deciding that I wanted to stop driving trucks, I started researching interface design. I had no degree and no skills apart from being an explosives operator. What could I possibly do?I literally stumbled upon UX design one night and noticed there was a conference soon in San Francisco, the UXDI15, so I bought a ticket and booked the flights. I had no idea what I would find, but it would be a great adventure anyway.What I found was the most incredible new world of possibility. I felt welcomed in a room full of warm hugs and acceptance. These are my people, UX people. Compassionate, empathetic, friendly, resourceful. Beautiful. I finally fit somewhere. Thank you, UX.I spent four days in awe, heard fantastic stories, met lots of clever people. Got an inappropriate tattoo…As soon as I arrived home I booked into UX Design at General Assembly. It wouldbe the first time I’d studied since high school, and meant 5.00 am wake-ups every Saturday morning to catch the train to Sydney – but hey, so worth it. I learned that the principles I stuck to fiercely during the control system designs were in fact correct UX principles. I was often right as it turns out.

I know what I am now

Since then I have designed two apps that each solve very real problems in society, and I am excited and utterly terrified to be forging ahead with the development of them. I have a small development team, and the savings of a house deposit to throw into a startup instead.I still work full time blowing things up. I’m still an exhausted single mum with three beautiful daughters, but fortunately I now have a decent man in my life. Still, I wake up terrified at 4.00 am most mornings. Am I mad? What do I know about UX? My computer dyslexia is improving, but it still doesn’t come naturally. I have interface rage constantly. Yes, I’m mad but determined. I will make this work, because, as I tell my daughters nearly every day, “Girls – you can achieve anything you set your mind to.” And they can. (Thanks for the great quote, Eminem.)Next time I blog it will be about how I accidentally became an entrepreneur, developed two-million-dollar apps, and managed to follow my dreams of drawing portraits of life in my cafe by the sea.I look forward to telling you all about it. ;-)

"So, what do we get for our money?" Quantifying the ROI of UX

"Dear Optimal Workshop

How do I quantify the ROI [return on investment] of investing in user experience?"

— Brian

Dear Brian,

I'm going to answer your question with a resounding 'It depends'. I believe we all differ in what we're willing to invest, and what we expect to receive in return. So to start with, and if you haven’t already, it's worth grabbing your stationery tools of choice and brainstorming your way to a definition of ROI that works for you, or for the people you work for.

I personally define investment in UX as time given, money spent, and people utilized. And I define return on UX as time saved, money made, and people engaged. Oh, would you look at that — they’re the same! All three (time, money, and humans) exist on both sides of the ROI fence and are intrinsically linked. You can’t engage people if you don’t first devote time and money to utilizing your people in the best possible way! Does that make sense?

That’s just my definition — you might have a completely different way of counting those beans, and the organizations you work for may think differently again.

I'll share my thoughts on the things that are worth quantifying (that you could start measuring today if you were so inclined) and a few tips for doing so. And I'll point you towards useful resources to help with the nitty-gritty, dollars-and-cents calculations.

5 things worth quantifying for digital design projects

Here are five things I think are worthy of your attention when it comes to measuring the ROI of user experience, but there are plenty of others. And different projects will most likely call for different things.

(A quick note: There's a lot more to UX than just digital experiences, but because I don't know your specifics Brian, the ideas I share below apply mainly to digital products.)

1. What’s happening in the call centre?

A surefire way to get a feel for the lay of the land is to look at customer support — and if measuring support metrics isn't on your UX table yet, it's time to invite it to dinner. These general metrics are an important part of an ongoing, iterative design process, but getting specific about the best data to gather for individual projects will give you the most usable data.

Improving an application process on your website? Get hard numbers from the previous month on how many customers are asking for help with it, go away and do your magic, get the same numbers a month after launch, and you've got yourself compelling ROI data.

Are your support teams bombarded with calls and emails? Has the volume of requests increased or decreased since you released that new tool, product, or feature? Are there patterns within those requests — multiple people with the same issues? These are just a few questions you can get answers to.

You'll find a few great resources on this topic online, including this piece by Marko Nemberg that gives you an idea of the effects a big change in your product can have on support activity.

2. Navigation vs. Search

This is a good one: check your analytics to see if your users are searching or navigating. I’ve heard plenty of users say to me upfront that they'll always just type in the search bar and that they’d never ever navigate. Funny thing is, ten minutes later I see the same users naturally navigating their way to those gorgeous red patent leather pumps. Why?

Because as Zoltán Gócza explains in UX Myth #16, people do tend to scan for trigger words to help them navigate, and resort to problem solving behaviour (like searching) when they can’t find what they need. Cue frustration, and the potential for a pretty poor user experience that might just send customers running for the hills — or to your competitors. This research is worth exploring in more depth, so check out this article by Jared Spool, and this one by Jakob Nielsen (you know you can't go wrong with those two).

3. Are people actually completing tasks?

Task completion really is a fundamental UX metric, otherwise why are we sitting here?! We definitely need to find out if people who visit our website are able to do what they came for.

For ideas on measuring this, I've found the Government Service Design Manual by GOV.UK to be an excellent resource regardless of where you are or where you work, and in relation to task completion they say:

"When users are unable to complete a digital transaction, they can be pushed to use other channels. This leads to low levels of digital take-up and customer satisfaction, and a higher cost per transaction."

That 'higher cost per transaction' is your kicker when it comes to ROI.

So, how does GOV.UK suggest we quantify task completion? They offer a simple (ish) recommendation to measure the completion rate of the end-to-end process by going into your analytics and dividing the number of completed processes by the number of started processes.

While you're at it, check the time it takes for people to complete tasks as well. It could help you to uncover a whole host of other issues that may have gone unnoticed. To quantify this, start looking into what Kim Oslob on UXMatters calls 'Effectiveness and Efficiency ratios'. Effectiveness ratios can be determined by looking at success, error, abandonment, and timeout rates. And Efficiency ratios can be determined by looking at average clicks per task, average time taken per task, and unique page views per task.

You do need to be careful not to make assumptions based on this kind of data— it can't tell you what people were intending to do. If a task is taking people too long, it may be because it’s too complicated ... or because a few people made themselves coffee in between clicks. So supplement these metrics with other research that does tell you about intentions.

4. Where are they clicking first?

A good user experience is one that gets out of bed on the right side. First clicks matter for a good user experience.

A 2009 study showed that in task-based user tests, people who got their first click right were around twice as likely to complete the task successfully than if they got their first click wrong. This year, researchers at Optimal Workshop followed this up by analyzing data from millions of completed Treejack tasks, and found that people who got their first click right were around three times as likely to get the task right.

That's data worth paying attention to.

So, how to measure? You can use software that records mouse clicks first clicks from analytics on your page, but it difficult to measure a visitor's intention without asking them outright, so I'd say task-based user tests are your best bet.

For in-person research sessions, make gathering first-click data a priority, and come up with a consistent way to measure it (a column on a spreadsheet, for example). For remote research, check out Chalkmark (a tool devoted exclusively to gathering quantitative, first-click data on screenshots and wireframes of your designs) and UserTesting.com (for videos of people completing tasks on your live website).

5. Resources to help you with the number crunching

Here's a great piece on uxmastery.com about calculating the ROI of UX.

Here's Jakob Nielsen in 1999 with a simple 'Assumptions for Productivity Calculation', and here's an overview of what's in the 4th edition of NN/G's Return on Investment for Usability report (worth the money for sure).

Here's a calculator from Write Limited on measuring the cost of unclear communication within organizations (which could quite easily be applied to UX).

And here's a unique take on what numbers to crunch from Harvard Business Review.

I hope you find this as a helpful starting point Brian, and please do have a think about what I said about defining ROI. I’m curious to know how everyone else defines and measures ROI — let me know!

Avoiding bias in the oh-so-human world of user testing

"Dear Optimal WorkshopMy question is about biasing users with the wording of questions. It seems that my co-workers and I spend too much time debating the wording of task items in usability tests or questions on surveys. Do you have any 'best practices' for wordings that evoke unbiased feedback from users?" — Dominic

Dear Dominic, Oh I feel your pain! I once sat through a two hour meeting that was dominated by a discussion on the merits of question marks!It's funny how wanting to do right by users and clients can tangle us up like fine chains in an old jewellery box. In my mind, we risk provoking bias when any aspect of our research (from question wording to test environment) influences participants away from an authentic response. So there are important things to consider outside of the wording of questions as well. I'll share my favorite tips, and then follow it up with a must-read resource or two.

Balance your open and closed questions

The right balance of open and closed questions is essential to obtaining unbiased feedback from your users. Ask closed questions only when you want a very specific answer like 'How old are you?' or 'Are you employed?' and ask open questions when you want to gain an understanding of what they think or feel. For example, don’t ask the participant'Would you be pleased with that?' (closed question). Instead, ask 'How do you feel about that?' or even better 'How do you think that might work?' Same advice goes for surveys, and be sure to give participants enough space to respond properly — fifty characters isn’t going to cut it.

Avoid using words that are linked to an emotion

The above questions lead me to my next point — don’t use words like ‘happy’. Don’t ask if they like or dislike something. Planting emotion based words in a survey or usability test is an invite for them to tell you what they think you want to hear . No one wants to be seen as being disagreeable. If you word a question like this, chances are they will end up agreeing with the question itself, not the content or meaning behind it...does that make sense? Emotion based questions only serve to distract from the purpose of the testing — leave them at home.

Keep it simple and avoid jargon

No one wants to look stupid by not understanding the terms used in the question. If it’s too complicated, your user might just agree or tell you what they think you want to hear to avoid embarrassment. Another issue with jargon is that some terms may have multiple meanings which can trigger a biased reaction depending on the user’s understanding of the term. A friend of mine once participated in user testing where they were asked if what they were seeing made them feel ‘aroused’. From a psychology perspective, that means you’re awake and reacting to stimuli.

From the user's perspective? I’ll let you fill in the blanks on that one. Avoid using long, wordy sentences when asking questions or setting tasks in surveys and usability testing. I’ve seen plenty of instances of overly complicated questions that make the user tune out (trust me, you would too!). And because people don't tend to admit their attention has wandered during a task, you risk getting a response that lacks authenticity — maybe even one that aims to please (just a thought...).

Encourage participants to share their experiences (instead of tying them up in hypotheticals)

Instead of asking your user what they think they would do in a given scenario, ask them to share an example of a time when they actually did do it. Try asking questions along the lines of 'Can you tell me about a time when you….?' or 'How many times in the last 12 months have you...?' Asking them to recall an experience they had allows you to gain factual insights from your survey or usability test, not hypothetical maybes that are prone to bias.

Focus the conversation by asking questions in a logical order

If you ask usability testing or survey questions in an order that doesn’t quite follow a logical flow, the user may think that the order holds some sort of significance which in turn may change the way they respond. It’s a good idea to ensure that the questions tell a story and follow a logical progression for example the steps in a process — don’t ask me if I’d be interested in registering for a service if you haven’t introduced the concept yet (you’d be surprised how often this happens!). For further reading on this, be sure to check out this great article from usertesting.com.

More than words — the usability testing experience as a whole

Reducing bias by asking questions the right way is really just one part of the picture. You can also reduce bias by influencing the wider aspects of the user testing process, and ensuring the participant is comfortable and relaxed.

Don’t let the designer facilitate the testing

This isn’t always possible, but it’s a good idea to try to get someone else to facilitate the usability testing on your design (and choose to observe if you like). This will prevent you from bringing your own bias into the room, and participants will be more comfortable being honest when the designer isn't asking the questions. I've seen participants visibly relax when I've told them I'm not the designer of a particular website, when it's apparent they've arrived expecting that to be the case.

Minimize discomfort and give observers a role

The more comfortable your participants are, with both the tester and the observer, the more they can be themselves. There are labs out there with two-way mirrors to hide observers, but in all honesty the police interrogation room isn’t always the greatest look! I prefer to have the observer in the testing room, while being conscious that participants may instinctively be uncomfortable with being observed. I’ve seen observer guidelines that insist observers (in the room) stay completely silent the entire time, but I think that can be pretty creepy for participants! Here's what works best (in my humble opinion).

The facilitator leads the testing session, of course, but the observer is able to pipe up occasionally, mostly for clarification purposes, and certainly join in the welcoming, 'How's the weather?' chit chat before the session begins. In fact, when I observe usability testing, I like to be the one who collects the participant from the foyer. I’m the first person they see and it’s my job to make them feel welcome and comfortable, so when they find out I'll be observing, they know me already. Anything you can do to make the participant feel at home will increase the authenticity of their responses.

A note to finish

At the end of the day the reality is we’re all susceptible to bias. Despite your best efforts you’re never going to eradicate it completely, but just being aware of and understanding it goes a long way to reducing its impacts. Usability testing is, after all, something we design. I’ll leave you with this quote from Jeff Sauro's must-read article on 9 biases to watch out for in usability testing:

"We do the best we can to simulate a scenario that is as close to what users would actually do .... However, no amount of realism in the tasks, data, software or environment can change the fact that the whole thing is contrived. This doesn't mean it's not worth doing."

"I need to upsell an item for charity during the online checkout process..."

"Dear Optimal WorkshopI need to add an upsell item for a charity group into the checkout process. This will include a 'Would you like to add this item?" question, and a tick box that validates the action in one click. Which step of the checkout process do you think this would be best on? Thanks in advance."— Mary

Dear MaryAbout a month ago, I found myself with some time to kill in Brisbane airport (Australia) before my flight home. I wandered on into a stationery store and it was seriously gorgeous, believe me. Its brick-walled interior had an astroturf floor and a back corner filled with design books — I could've spent hours in there.I selected a journal that facilitates daily ranting through guided questions, and made my way to the counter to pay.

Just as I was about to part with my hard-earned dollars, the sales assistant offered me a charity upsell in the form of a 600ml bottle of water for $2 (AUD). Now, I don’t know how familiar you are with Australian domestic airports, but a bottle of water bought from the airport costing less than an absurdly expensive $5 is something I’d written off as a unicorn!Yes, that’s right.

$5 for WATER is considered normal, and this nice man was offering it to me for $2, in a coloured bottle of my choice, complete with that feel-good feeling of giving to charity! I left the store feeling pretty proud of myself and silently had a giggle at people who were buying bottled water elsewhere.

Getting the balance right

Charity upselling at the check out can be a tricky thing. If we get it wrong, we not only fail to raise money for the charity, but we also risk annoying our customers at a moment we want them to be particularly happy with us. The experience I had at the airport is one that I would describe as near perfect. Not all experiences are as positive. It falls down when people start feeling pressured or tricked; when it turns into an ambush.I like the approach you’re looking at.

It’s non-threatening and seamless for the user. So, where should you position it in the checkout?Online checkout is a process like any other: it follows a uniform, often-linear order, and each step involves an action that moves things forward.From my vast online shopping experience (and I do mean vast), I've observed that the generic checkout process looks something like this:

- Add item to cart

- View cart (option to skip and proceed straight to checkout is also common)

- Proceed to checkout

- Sign in / Create account / Guest checkout

- Enter billing address

- Enter / Confirm shipping address

- Enter payment details

- Review purchase

- Make payment

- Confirmation / Payment decline screen

There are two ways that I would consider approaching this and it largely depends on the actual charity upsell item itself.

If you're offering a product to purchase for charity, offer early

If we're talking about the equivalent of my water bottle (offering a product), then I say introduce it earlyin the checkout process (either Step 1 or 2). Why? Because the customer is still in buying mode.

Once they click ‘Proceed to checkout’, they transition and theirfocus shifts tothe business end of their purchase. The stationery store at Brisbane Airport offered the water before telling me how much I owed them. I hadn't quite got to the real world version of checkout mode, which for me was Where did I put my debit card? mode. I quite like the way Oxfam Australia handles the charity upsell by including an 'Add to your gift' button (screen 1) which takes you to the charity upsell option (screen 2) and guides you back to the previous screen, all before checkout.

If you're asking for a donation to charity, ask later

Now, if we'retalking about a donation, such as rounding the purchase price up to the nearest dollar, or asking straight out, it’s a slightly different story. I'd say addthe charity upsell option when they first review their whole intended purchase. It might be before confirming the shipping address, or even just before confirming payment details. They've got money on the brain, and they haven't quite sealed the deal. And it can only be good for the charity if the customer can easily see how small the requested donation is compared to their entire purchase (ahh, the art of persuasion...).

Once they start typing in their payment details, they're essentially signing on the dotted line and entering into a contract with you. So there's no asking after that.David Moth published an interesting article discussing upselling and the online checkout process that's worth a look, so do check it out.In the end, this is something that you'll still want to testwith users, and ultimately it will be up to them. If you have scope, try out a few different options and see which results in more sales. Hopefully this post has given you a good place to start.

All the best Mary!

Are small links more attractive to people as icons or text?

"Dear Optimal Workshop

How do you make a small link attractive to people (icon vs. text)?"

— Cassie

Dear Cassie,

I'm going to dive straight into this interesting question with a good old game of Pros and Cons, and then offer a resolution of sorts, with a meandering thought or two along the way. Let's kick things off with Team Icon.

The good side of icons: A picture is worth a 1000 words

When shopping online, the number above the little shopping trolley icon tells me how badly behaved I’ve been, and if I click on it, I know I’ll get to gleefully review all the shoes I've selected so far. There’s a whole heap of icons out there like this that people have absorbed and can use without thinking twice. Marli Mesibov wrote a fantastic article on the use of icons for UX Booth on the use of icons that is well worth a look. Marli discusses how they work well on small screens, which is a definite bonus when you’re on the go! Young children who aren’t yet literate can easily figure out how to open and play Angry Birds on their parent’s smartphones thanks to icons. And icons also have a great capacity for bridging language barriers.

The not so good side of icons: We’re too old for guessing games

On the flipside, there are some issues that may huff and puff and blow that cute little home icon down. Starting with there being no consistent standard for them. Sure, there are a handful that are universal like home and print, but beyond that it seems to be a free-for-all. Icons are very much in the hands of the designer and this leaves a lot of room for confusion to grow like bacteria in a badly maintained office refrigerator. Difficult to understand icons can also seriously hinder a user’s ability to learn how to use your website or application. When icons don't communicate what they intend, well, you can guess what happens. In a great piece advocating for text over icons, Joshua Porter writes about an experience he had:

"I have used this UI now for a week and I still have do a double-take each time I want to navigate. I’m not learning what the icons mean. The folder icon represents 'Projects', which I can usually remember (but I think I remember it because it’s simply the first and default option). The second icon, a factory, is actually a link to the 'Manage' screen, where you manage people and projects. This trips me up every time."

If people can't pick up the meaning of your icons quickly and intuitively, they may just stop trying altogether. And now, over to Team Label.

The good side of text: What you see is what you get

Sometimes language really is the fastest vehicle you've got for delivering a message. If you choose the right words to label your links, you'll leave the user with very little doubt as to what lies beneath. It’s that simple. Carefully-considered and well-written labels can cut through the noise and leave minimal ambiguity in their wake. Quoting Joshua Porter again: "Nothing says 'manage' like 'manage'. In other words, in the battle of clarity between icons and labels, labels always win."

The not so good side of text: Your flat shoe is my ballet pump

Text labels can get messy and be just as confusing as unfamiliar icons! Words and phrases sometimes don’t mean the same thing to different people. One person’s flat enclosed shoe may be another person’s ballet pump, and the next person may be left scratching their head because they thought pumps were heels and all they wanted was a ballet flat! Text only labels can also become problematic if there isn’t a clear hierarchy of information, and if you have multiple links on one page or screen. Bombarding people with a page of short text links may make it difficult for them to find a starting point. And text may also hold back people who speak other languages.

The compromise: Pair icons up with text labels

Because things are always better when we work together! Capitalise on the combined force of text and icons to solve the dilemma. And I don’t mean you should rely on hovers — make both text and icon visible at all times. Two great examples are Google Apps (because nothing says storage like a weird geometric shape...) and the iPhone App store (because the compass and magnifying glass would pose an interesting challenge without text...):

So what comes next? (You can probably guess what I'm going to say)

Whatever you decide to run with, test it. Use whatever techniques you have on hand to test all three possibilities — icons only, text only, and icons and text — on real people. No Pros and Cons list, however wonderful, can beat that. And you know, the results will probably surprise you. I ran a quick study recently using Chalkmark to find out where people on the ASOS women's shoes page would click to get to the homepage (and yes, I can alway find ways to make shoe shopping an integral part of my job). 28 people responded, and...

...a whopping 89% of them clicked the logo, just 7% clicked the home icon, and just one person (the remaining 4%) clicked the label 'Home'. Enough said. Thanks for your question Cassie. To finish, here's some on-topic (and well-earned) comic relief (via @TechnicallyRon)

Card Sorting outside UX: How I use online card sorting for in-person sociological research

Hello, my name is Rick and I’m a sociologist. All together, “Hi, Rick!” Now that we’ve got that out of the way, let me tell you about how I use card sorting in my research. I'll soon be running a series of in-person, moderated card sorting sessions. This article covers why card sorting is an integral part of my research, and how I've designed the study toanswer specific questions about two distinct parts of society.

Card sorting to establish how different people comprehend their worlds

Card sorting,or pile sorting as it’s sometimes called, has a long history in anthropology, psychology and sociology. Anthropologists, in particular, have used it to study how different cultures think about various categories. Researchers in the 1970s conducted card sorts to understand how different cultures categorize things like plants and animals. Sociologists of that era also used card sorts to examine how people think about different professions and careers. And since then, scholars have continued to use card sorts to learn about similar categorization questions.

In my own research, I study how different groups of people in the United States imagine the category of 'religion'. Asthose crazy 1970s anthropologists showed, card sorting is a great way to understand how people cognitively understand particular social categories. So, in particular,I’m using card sorting in my research to better understand how groups of people with dramatically different views understand 'religion' — namely, evangelical Christians and self-identified atheists. Thinkof it like this. Some people say that religion is the bedrock of American society.

Others say that too much religion in public life is exactly what’s wrong with this country. What's not often considered is these two groups oftenunderstand the concept of 'religion' in very different ways. It’s like the group of blind men and the elephant: one touches the trunk, one touches the ears, and one touches the tail. All three come away with very different ideas of what an elephant is. So you could say that I study how different people experience the 'elephant' of religion in their daily lives. I’m doing so using primarily in-person moderated sorts on an iPad, which I’ll describe below.

How I generated the words on the cards

The first step in the process was to generate lists of relevant terms for my subjects to sort. Unlike in UX testing, where cards for sorting might come from an existing website, in my world these concepts first have to be mined from the group of people being studied. So the first thing I did was have members of both atheist and evangelical groups complete a free listing task. In a free listing task, participants simply list as many words as they can that meet the criteria given. Sets of both atheist and evangelical respondents were given the instructions: "What words best describe 'religion?' Please list as many as you can.” They were then also asked to list words that describe 'atheism', 'spirituality', and 'Christianity'.

I took the lists generated and standardizedthem by combining synonyms. For example, some of my atheists used words like 'ancient', 'antiquated', and 'archaic' to describe religion. SoI combined all of these words into the one that was mentioned most: 'antiquated'. By doing this, I created a list of the most common words each group used to describe each category. Doing this also gave my research another useful dimension, ideal for exploring alongside my card sorting results. Free lists can beanalyzed themselves using statistical techniques likemulti-dimensional scaling, so I used this technique for apreliminary analysis of the words evangelicals used to describe 'atheism':

Now that I’m armed with these lists of words that atheist and evangelicals used to describe religion, atheism etc., I’m about to embark on phase two of the project: the card sort.

Why using card sorting software is a no-brainer for my research

I’ll be conducting my card sorts in person, for various reasons. I have relatively easy access to the specific population that I’m interested in, and for the kind of academic research I’m conducting, in-person activities are preferred. In theory, I could just print the words on some index cards and conduct a manual card sort, but I quickly realized that a software solution would be far preferable, for a bunch of reasons.

First of all, it's important for me to conductinterviews in coffee shops and restaurants, and an iPad on the table is, to put it mildly, more practical than a table covered in cards — no space for the teapot after all.

Second, usingsoftwareeliminates the need for manual data entry on my part. Not only is manual data entry a time consuming process, but it also introduces the possibly of data entry errors which may compromise my research results.

Third, while the bulk of the card sorts are going to be done in person, having an online version will enable meto scale the project up after the initial in-person sorts are complete. The atheist community, in particular, has a significant online presence, making a web solution ideal for additional data collection.

Fourth, OptimalSort gives the option to re-direct respondents after they complete a sort to any webpage, which allows multiple card sorts to be daisy-chained together. It also enables card sorts to be easily combined with complex survey instruments from other providers (e.g. Qualtrics or Survey Monkey), so card sorting data can be gathered in conjunction with other methodologies.

Finally, and just as important, doing card sorts on a tablet is more fun for participants. After all, who doesn’t like to play with an iPad? If respondents enjoy the unique process of the experiment, this is likely to actually improve the quality of the data, andrespondents are more likely to reflect positively on the experience, making recruitment easier. And a fun experience also makes it more likely that respondents will complete the exercise.

What my in-person, on-tablet card sorting research will look like

Respondents will be handed an iPad Air with 4G data capability. While the venues where the card sorts will take place usually have public Wi-Fi networks available, these networks are not always reliable, so the cellular data capabilities are needed as a back-up (and my pre-testing has shown that OptimalSort works on cellular networks too).

The iPad’s screen orientation will be locked to landscape and multi-touch functions will be disabled to prevent respondents from accidentally leaving the testing environment. In addition, respondents will have the option of using a rubber tipped stylus for ease of sorting the cards. While I personally prefer to use a microfiber tipped stylus in other applications, pre-testing revealed that an old fashioned rubber tipped stylus was easier for sorting activities.

When the respondent receives the iPad, the card sort first page with general instructions will already be open on the tablet in the third party browser Perfect Web. A third party browser is necessary because it is best to run OptimalSort locked in a full screen mode, both for aesthetic reasons and to keep the screen simple and uncluttered for respondents. Perfect Web is currently the best choice in the ever shifting app landscape.

I'll give respondents their instructions and then go to another table to give them privacy (because who wants the creepy feeling of some guy hanging over you as you do stuff?). Altogether, respondents will complete two open card sorts and a fewsurvey-style questions, all chained together by redirect URLs. First, they'll sort 30 cards into groups based on how they perceive 'religion', and name the categories they create. Then, they'll complete a similar card sort, this time based on how they perceive 'atheism'.

Both atheist and evangelicals will receive a mixture of some of the top words that both groups generated in the earlier free listing tasks. To finish, they'll answer a few questions that will provide further data on how they think about 'religion'. After I’ve conducted these card sorts with both of my target populations, I’ll analyze the resulting data on its own and also in conjunction with qualitative data I’ve already collected via ethnographic research and in-depth interviews. I can't wait, actually. In a few months I’ll report back and let you know what I’ve found.

No results found.