The key purpose of running a card sort is to learn something new about how people conceptualize and organize the information that’s found on your website. The insights you gain from running a card sort can then help you develop a site structure with content labels or headings that best represent the way your users think about this information. Card sorts are in essence a simple technique, however it’s the details of the sort that can determine the quality of your results.

Adding context to cards in OptimalSort – descriptions, links and images

In most cases, each item in a card sort has only a short label, but there are instances where you may wish to add additional context to the items in your sort. Currently, the cards tab in OptimalSort allows you to include a tooltip description, a link within the tooltip description or to format the card as an image (with or without a label).

We generally don’t recommend using tooltip descriptions and links, unless you have a specific reason to do so. It’s likely that they’ll provide your participants with more information than they would normally have when navigating your website, which may in turn influence your results by leading participants to a particular solution.

Legitimate reasons that you may want to use descriptions and links include situations where it’s not possible or practical to translate complex or technical labels (for example, medical, financial, legal or scientific terms) into plain language, or if you’re using a card sort to understand your participants’ preferences or priorities.

If you do decide to include descriptions in your sort, it’s important that you follow the same guidelines that you would otherwise follow for writing card labels. They should be easy for your participants to understand and you should avoid obvious patterns, for example repeating words and phrases, or including details that refer to the current structure of the website.

A quick survey of how card descriptions are used in OptimalSort

I was curious to find out how often people were including descriptions in their card sorts, so I asked our development team to look into this data. It turns out that around 15% of cards created in OptimalSort have at least some text entered in the description field. In order to dig into the data a bit further, both Ania and I reviewed a random sample of recent sorts and noted how descriptions were being used in each case.

We found that out of the descriptions that we reviewed, 40% (6% of the total cards) had text that should not have impacted the sort results. Most often, these cards simply had the card label repeated in the description (to be honest, we’re not entirely sure why so many descriptions are being used this way! But it’s now in our roadmap to stop this from happening — stay tuned!). Approximately 20% (3% of the total cards) used descriptions to add context without obviously leading participants, however another 40% of cards have descriptions that may well lead to biased results. On occasion, this included linking to the current content or using what we assumed to be the current top level heading within the description.

Testing the effect of card descriptions on sort results

So, how much influence could potentially leading card descriptions have on the results of a card sort? I decided to put it to the test by running a series of card sorts to compare the effect of different descriptions. As I also wanted to test the effect of linking card descriptions to existing content, I had to base the sort on a live website. In addition, I wanted to make sure that the card labels and descriptions were easily comprehensible by a general audience, but not so familiar that participants were highly likely to sort the cards in a similar manner.

I selected the government immigration website New Zealand Now as my test case. This site, which provides information for prospective and new immigrants to New Zealand, fit the above criteria and was likely unfamiliar to potential participants.

Navigating the New Zealand Now website

When I reviewed the New Zealand Now site, I found that the top level navigation labels were clear and easy to understand for me personally. Of course, this is especially important when much of your target audience is likely to be non-native English speaking! On the whole, the second level headings were also well-labeled, which meant that they should translate to cards that participants were able to group relatively easily.

There were, however, a few headings such as “High quality” and “Life experiences”, both found under “Study in New Zealand”, which become less clear when removed from the context of their current location in the site structure. These headings would be particularly useful to include in the test sorts, as I predicted that participants would be more likely to rely on card descriptions in the cases where the card label was ambiguous.

I selected 30 headings to use as card labels from under the sections “Choose New Zealand”, “Move to New Zealand”, “Live in New Zealand”, “Work in New Zealand” and “Study in New Zealand” and tweaked the language slightly, so that the labels were more generic.

I then created four separate sorts in OptimalSort:Round 1: No description: Each card showed a heading only — this functioned as the control sort

Round 2: Site section in description: Each card showed a heading with the site section in the description

Round 3: Short description: Each card showed a heading with a short description — these were taken from the New Zealand Now topic landing pages

Round 4:Link in description: Each card showed a heading with a link to the current content page on the New Zealand Now website

For each sort, I recruited 30 participants. Each participant could only take part in one of the sorts.

What the results showed

An interesting initial finding was that when we queried the participants following the sort, only around 40% said they noticed the tooltip descriptions and even fewer participants stated that they had used them as an aid to help complete the sort.

Participant recognition of descriptions

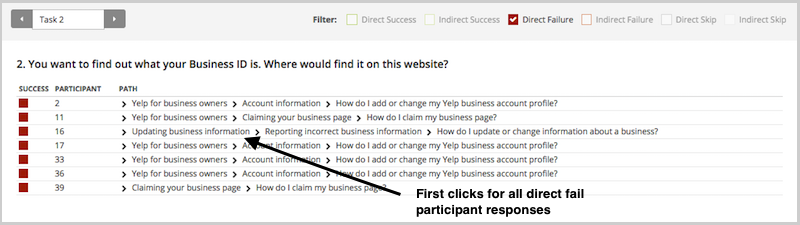

Of course, what people say they do does not always reflect what they do in practice! To measure the effect that different descriptions had on the results of this sort, I compared how frequently cards were sorted with other cards from their respective site sections across the different rounds.Let’s take a look at the “Study in New Zealand” section that was mentioned above. Out of the five cards in this section,”Where & what to study”, “Everyday student life” and “After you graduate” were sorted pretty consistently, regardless of whether a description was provided or not. The following charts show the average frequency with which each card was sorted with other cards from this section. For example in the control round, “Where & what to study” was sorted with “After you graduate” 76% of the time and with “Everyday day student life” 70% of the time, but was sorted with “Life experiences” or “High quality” each only 10% of the time. This meant that the average sort frequency for this card was 42%.

Untitled chartCreate bar charts

On the other hand, the cards “High quality” and “Life experiences” were sorted much less frequently with other cards in this section, with the exception of the second sort, which included the site section in the description.These results suggest that including the existing site section in the card description did influence how participants sorted these cards — confirming our prediction! Interestingly, this round had the fewest number of participants who stated that they used the descriptions to help them complete the sort (only 10%, compared to 40% in round 3 and 20% in round 4).Also of note is that adding a link to the existing content did not seem to increase the likelihood that cards were sorted more frequently with other cards from the same section. Reasons for this could include that participants did not want to navigate to another website (due to time-consciousness in completing the task, or concern that they’d lose their place in the sort) or simply that it can be difficult to open a link from the tooltip pop-up.

What we can take away from these results

This quick investigation into the impact of descriptions illustrates some of the intricacies around using additional context in your card sorts, and why this should always be done with careful consideration. It’s interesting that we correctly predicted some of these results, but that in this case, other uses of the description had little effect at all. And the results serve as a good reminder that participants can often be influenced by factors that they don’t even recognise themselves!If you do decide to use card descriptions in your cards sorts, here are some guidelines that we recommend you follow:

- Avoid repeating words and phrases, participants may sort cards by pattern-matching rather than based on the actual content

- Avoid alluding to a predetermined structure, such as including references to the current site structure

- If it’s important that participants use the descriptions to complete the sort, you should mention this in your task instructions. It may also be worth asking them a post-survey question to validate if they used them or not

We’d love to hear your thoughts on how we tested the effects of card descriptions and the results that we got. Would you have done anything differently?Have you ever completed a card sort only to realize later that you’d inadvertently biased your results? Or have you used descriptions in your card sorts to meet a genuine need? Do you think there’s a case to make descriptions more obvious than just a tooltip, so that when they are used legitimately, most participants don’t miss this information?

Let us know by leaving a comment!