Usability testing is one of the best ways to measure how easy and intuitive to use something is by testing it with real people. You can read about the basics of usability testing here.

Earlier this year, a small team within Optimal Workshop completely redesigned the company blog. More than anything, we wanted to create something that was user-friendly for our readers and would give them a reason to return. I was part of that team, and we ran numerous sessions interviewing regular readers as well as people unfamiliar with our blog. We also ran card sorts, tree tests and other studies to find out all we could about how people search for UX content. Unsurprisingly, one of the most valuable activities we did was usability testing – sitting down with representative users and watching them as they worked through a series of tasks we provided. We asked general questions like “Where would you go to find information about card sorting”, and we also observed them as they searched through our website for learning content.

By stripping away any barriers between ourselves and our users and observing them as they navigated through our website and learning resources, as well as those of other companies, we were able to build a blog with these people’s behaviors and motivations in mind.

Usability testing is an invaluable research method, and every user researcher should be able to run sessions effectively. Here are 5 tips for doing so, in no particular order.

1. Clarify your goals with stakeholders

Never go into a usability test blind. Before you ever sit down with a participant, make sure you know exactly what you want to get out of the session by writing down your research goals. This will help to keep you focused, essentially giving you a guiding light that you can refer back as you go about the various logistical tasks of your research. But you also need to take this a step further. It’s important to make sure that the people who will utilize the results of your research – your stakeholders – have an opportunity to give you their input on the goals as early as possible.

If you’re running usability tests with the aim of creating marketing personas, for example, meet with your organization’s marketing team and figure out the types of information they need to create these personas. In some cases, it’s also helpful to clarify how you plan to gather this data, which can involve explaining some of the techniques you’re going to use.

Lastly, find out how your stakeholders plan to use your findings. If there are a lot of objectives, organize your usability test so you ask the most important questions first. That way, if you end up going off track or you run out of time you’ll have already gathered the most important data for your stakeholders.

2. Be flexible with your questions

A list of pre-prepared questions will help significantly when it comes time to sit down and run your usability testing sessions. But while a list is essential, sometimes it can also pay to ‘follow your nose’ and steer the conversation in a (potentially) more fruitful direction.

How many times have you been having a conversation with a friend over a drink or dinner, only for you both to completely lose track of time and find yourselves discussing something completely unrelated? While it’s not good practice to let your usability testing sessions get off track to this extent, you can surface some very interesting insights by paying close attention to a user’s behavior and answers during a testing session and following interesting leads.

Ideally, and with enough practice, you’ll be able to answer your core (prepared) questions and ask a number of other questions that spring to mind during the session. This is a skill that takes time to master, however.

3. Write a script for your sessions

While a usability test script may sound like a fancy name for your research questions, it’s actually a document that’s much more comprehensive. If you prepare it correctly (we’ll explain how below), you’ll have a document that you can use to capture in-depth insights from your participants.

Here are some of the key things to keep in mind when putting together your script:

- Write a friendly introduction – It may sound obvious, but taking the time to come up with a friendly, warm introduction will get your sessions off to a much better start. The bonus of writing it down is that you’re far less likely to forget it!

- Ask to record the session – It’s important to record your session (whether through video or audio), as you’ll want to go back later and analyze any details you may have missed. This means asking for explicit permission to record participants. In addition to making them feel more comfortable, it’s just good practice to do so.

- Allocate time for the basics – Don’t dive into the complex questions first, use the first few minutes to gather basic data. This could be things like where they work and their familiarity with your organization and/or product.

- Encourage them to explain their thought process – “I’d like you to explain what you’re doing as you make your way through the task”. This simple request will give you an opportunity to ask follow-up questions that you otherwise may not have thought to ask.

- Let participants know that they’re not being tested – Whenever a participant steps into the room for a test, they’re naturally going to feel like they’re being tested. Explain that you’re testing the product, not them. It’s also helpful to let them know that there are no right or wrong answers. This is an important step if you want to keep them relaxed.

It’s often easiest to have a document with your script printed out and ready to go for each usability test.

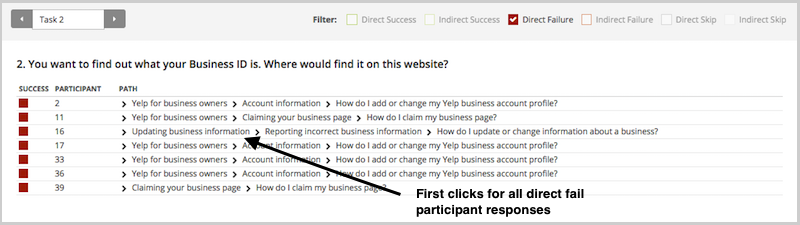

4. Take advantage of software

You’d never see a builder without a toolbox full of a useful assortment of tools. Likewise, software can make the life of a user research that much easier. The paper-based ways of recording information are still perfectly valid, but introducing custom tools can make both the logistics of user research and the actual sessions themselves much easier to manage.

Take a tool like Calendly, for example. This is a powerful piece of scheduling software that almost completely takes over the endless back and forth of scheduling usability tests. Calendly acts as a middle man between you and your participants, allowing you to set the times you’re free to host usability tests, and then allowing participants to choose a session that suits them from these times.

Our very own Reframer makes the task of running usability tests and analyzing insights that much easier. During your sessions, you can use Reframer to take comprehensive notes and apply tags like “positive” or “struggled” to different observations. Then, after you’ve concluded your tests, Reframer’s analysis function will help you understand wider themes that are present across your participants.

There’s another benefit to using a tool like Reframer. Keeping all of your notes in place will mean you easily pull up data from past research sessions whenever you need to.

5. Involve others

Usability tests (and user interviews, for that matter) are a great opportunity to open up research to your wider organization. Whether it’s stakeholders, other members of your immediate team or even members of entirely different departments, giving them the chance to sit down with users will show them how their products are really being used. If nothing else, these sessions will help those within your organization build empathy with the people they’re building products for.

There are quite a few ways to bring others in, such as:

- To help you set up the research – This can be a helpful exercise for both you (the researcher) and the people you’re bringing in. Collaborate on the overarching research objectives, ask them what types of results they’d like to see and what sort of tasks they think could be used to gather these results.

- As notetakers – Having a dedicated notetaker will make your life as a researcher significantly easier. This means you’ll have someone to record any interesting observations while you focus on running the session. Just let them know what types of notes you’d like to see.

- To help you analyze the data – Once you’ve wrapped up your usability testing sessions, bring others in to help analyze the findings. There’s a good chance that an outside perspective will catch something you may miss. Also, if you’re bringing stakeholders into the analysis stage, they'll get a clearer picture of what it means and where the data came from.

There are myriad other tips and best practices to keep in mind when usability testing, many of which we cover in our introductory page. Important considerations include taking good quality notes, carefully managing participants during the session (not giving them too much guidance) and remaining neutral throughout when answering their questions. If you feel like we’ve missed any really important points, feel free to leave a comment!

Read more