New release: Test any website or web app. No code needed.

Learn more

Remember that you are the one who is doing the thinking, not the technique… you are the one who puts it all together into a great solution. Follow your instincts, take some risks, and try new approaches.

Donna Spencer (the creator of the card sorting methodology)

Card sorting is a research technique that helps you discover how people understand and categorize information, and ensures you create an information architecture that matches users’ expectations. In a card sort, participants sort labeled cards into groups. You can then use the results of your participants’ card sorts to give you ideas about how to group and label the information on your website* in a way that makes the most sense to your audience.

Card sorting is useful when you want to:

*We’ve used the word ‘website’ here and throughout this guide, but you could be organizing information in an app, an intranet, a TV program guide, a form, a board game or anything where information might be organized in a structure to make sense.

Card sorting involves creating a set of cards that each represent a concept or item, and asking people to group the cards in a way that makes sense to them.

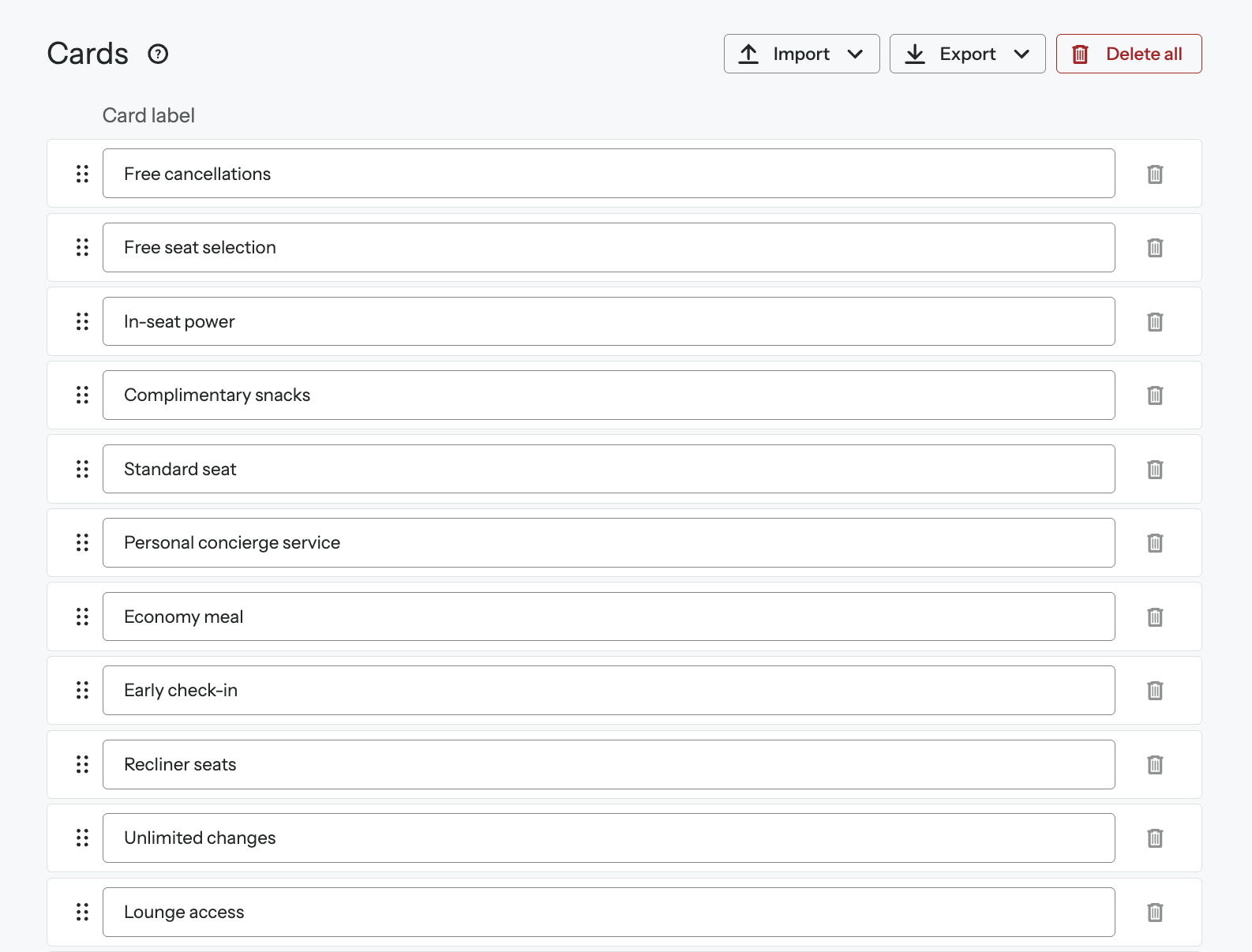

Let’s say you’re working on redesigning an airlines website and you want to understand how your users categorize the different content and information that will be on the site. You’ll add in a bunch of cards (these could be text or images, but more on that later) which will look like this in setup:

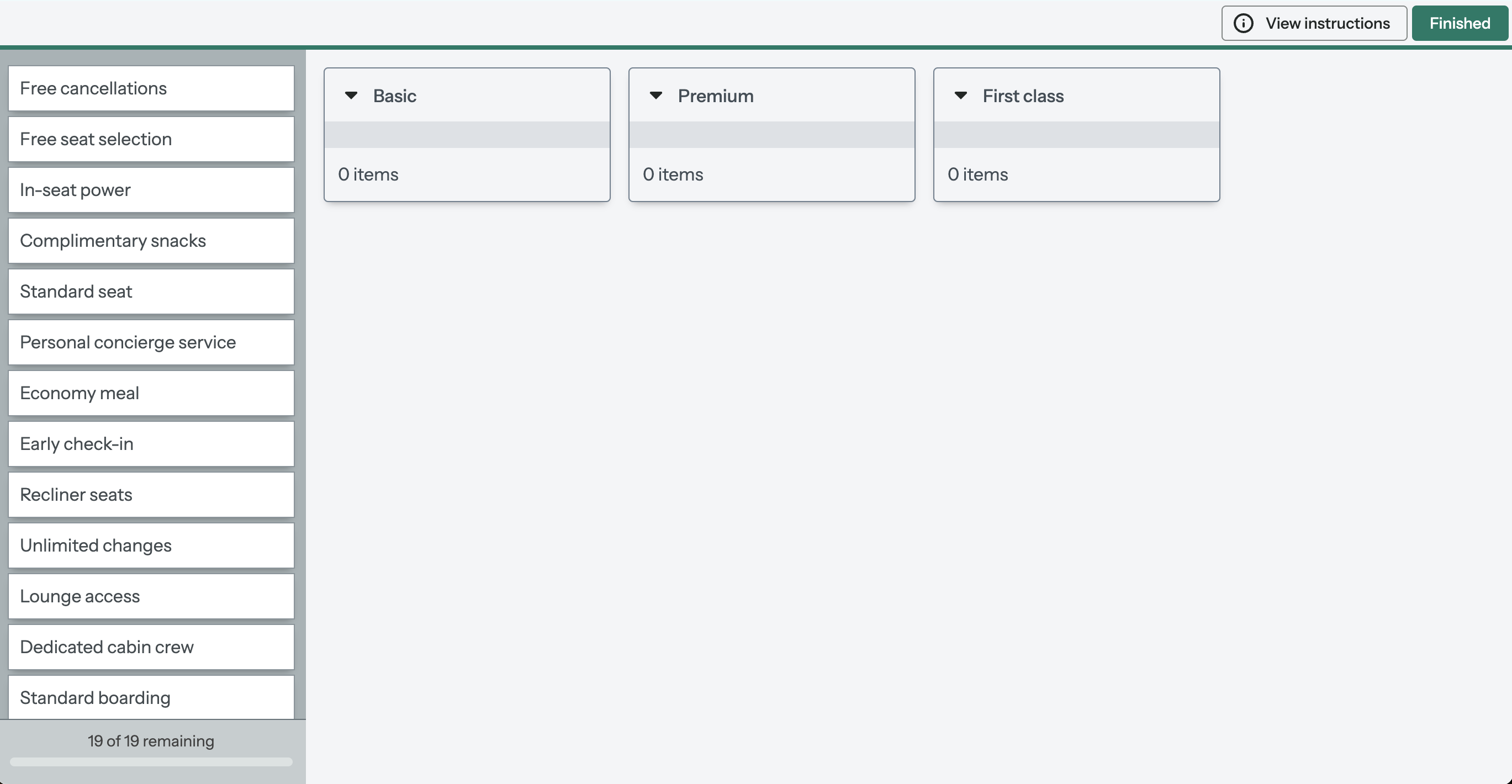

And look like this to your study participants:

There are three approaches to card sorting: open, closed and hybrid. Which approach you use will depend on what you want to find out. We’ll go into further detail on each method below, but here’s a high-level introduction to how they work:

Card sorting is most useful when you’ve already got the information or content you need to organize, but you’re just not sure exactly how to organize it.

Using the city council website as an example, you want to redesign how information is grouped together across the entire site. Card sorting will help you discover where people would commonly expect to find a category on your website.

You simply present them with a list of cards containing the names of items, concepts or labels and have users sort them into groups that make sense to them.

While card sorting is typically used in the early stages of the design process, when there’s no fixed information architecture (IA), it’s also common to use the technique to make changes to an IA, later down the line.

The three card sorting techniques — open, closed, and hybrid — will each tell you something different about how people understand and group your information. Choosing the right technique at the right time is key to gathering high-quality, relevant data to inform your design decisions.

It’s also the best place to start. Let’s take a deep dive into each of the card sorting methods.